by Akinwande Jordan

Hijack’ 93 has an engine problem.

On October 25, 1993, Caishen, the Chinese god of fortune and prosperity, forgot to warn Rong Yiren, the former vice president of China, about the blood-curling event that was to take place on Airbus 310 en route to Abuja that possibly humid morning in the erstwhile capital of the nation.

He alongside Professor Bolaji Akinyemi , a former Minister of External Affairs, Garba Duba – a decorated retired Major General and one-time military governor and Suleiman Saidu, former Director-General of the Federal Environmental Protection Agency (FEPA) did not envisage what was probably at the time the worst Monday morning they had ever experienced. I resonate with their pain because watching Hijack ’93 wasn’t dissimilar to having a terrifying Monday morning in the frenzied city of Lagos.

Robert O. Peters (30 Days In Atlanta) bursts out the gate with his directorial katanas to slice air here—scalar, kinetic, filled with the force to entertain and document history. Our thriller opens with time and place: LAGOS, 1993, and sends us into a timeline devoid of any recognition.

An establishing shot and artistic licence ushers us into the gears of a revolution; Mallam Jerry Yusuf (Sam Dede), leader of the Movement for the Actualization of Democracy or MAD men, rallies his young militia with a call to arms before choosing the would-be hijackers; Skipper/Omar (Nnamdi Agbo), Eruku/Kayode (Adam Garba), Owiwi/Ben (Allison Emmanuel) and Iku/Dayo (Oluwaseyi Akinsola) arbitrarily with the rebellious intention to divert to flight from Lagos to Abuja to Frankfurt, Germany.

Perhaps the primary purpose of this scene is to contextualise the historical event —to give it the formal treatment of a rising action without delineating the broader political chain reactions plaguing Nigeria at the time. That is no cinematic lese majeste; liberties are taken all the time in service of entertainment. However, the scene simply signifies nothing. It blitzes past you, leaving no vestiges. Only an enormous question mark and a concerning “I see” followed by abject confusion.

Each act relies solely on the weight of its lead actors. Close-up shots, often purposefully deployed to create an emotional tether with characters as the plot unfolds, are launched here in quick succession to mine palpable suspense and pathos with characters that have given us little to work with. But the result seems to be wanting the actors to take a few steps back.

Abysmal attempts are made at interspersing the events on the plane with reaction of the masses by creating a bevy of disparate people gathered around a radio reporting the hijack to shabbily debate moral dilemmas within the context of political turmoil.

This is portrayed as a microcosm of the Nigerian condition — if we weren’t provided with the benefit of newspaper archives and history books, we might not get the sense that this was one of the most volatile years in Nigeria’s quest for a democratic system of government. We are only told through blatant exposition.

Anachronistic lines like “all lives matter” hit your ears like rapid slaps, but they pale in comparison to how each scene attempts to “humanise” the hijackers and place them in an ethical framework of the classic dilemma and the greater good theory.

But it’s difficult to determine a moral calculus when every character is rudderless and fluctuating across plot points. It’s almost baffling to believe this is a film with a runtime under 2 hours, given the elongated second act that feels like a miscalculation. Elongated and lethargic, dislocated from the initial guns-blazing sequence it began with. You feel the scenes tarry — everything is happening, but nothing is actually moving towards anything worth waiting for.

Chiefly, what is missing in Hijack ’93 is an engine. A narrative engine that propels the motion of a story from point A to point B rhythmically. It’s the stuff of Aesop’s fables and parables. Action is eloquence, and Hijack ’93 is severely ineloquent. It says it is suspenseful. It promises the stakes are high. It says you can start a revolution from your bedroom with this film. And it chuckles mischievously at your face as you sit there for the gratuitous spree of noise-making.

All is not lost. However, Nnamdi Agbo stands out amongst the stars. He does what he can with the material — balancing every line, no matter how on-the-nose, with an actor’s conviction. Very rarely do you see shining gems with panache in the heaps of dust, but Nnamdi Agbo is one to watch.

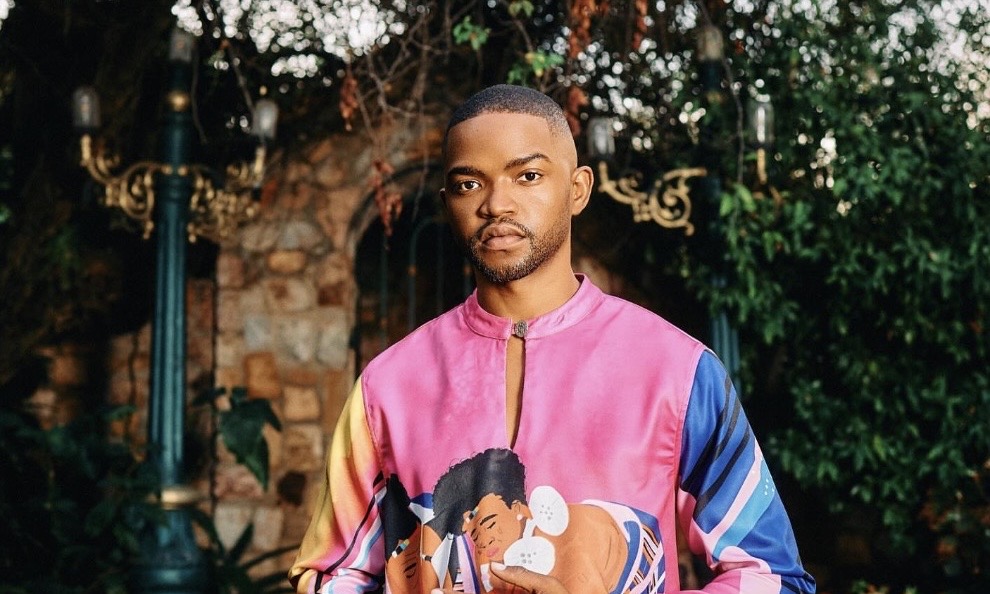

Regrettably, he seems to be the only redeeming quality the film possesses. John Dumelo, Efe Iwara, Adam Garba, and the rest of the ensemble do their very best, but they are victims of directorial vision or under-directing.

The umbrage one might take from this film is the availability of abundant films, albeit Hollywood productions, with this premise coupled with the historical precedence that could have served as a guiding light.

Accuracy does not make a good historical drama/thriller, so it might be nit-picky and borderline anti-cinema to indict a film on the basis of that. A film should be adjudicated and appreciated on the merits of its aesthetic, style, structure and, if you are feeling academic, philosophy. Unfortunately, this – pardon the pun – lands tediously and featureless.

When it comes to how we film history, our frame of reference is marred by tales of oppressive victors or an overt lack of records, but this does not justify the hokum we produce in the name of portraying significant historical events. It is not enough that it is done; it must be done well. Liberties and licences can be taken, but only in service of the story.

Not to spoon-feed the audience, who have the responsibility of critical thinking. Not to make a film because “Wouldn’t this be cool? It looks like an action film.” The real story of the Hijacking of Airbus 310 is memorably more tragic and sorrowful and deserving of something better. But Hijack ’93 is a repetition of tragedy and farce.