by Angel Nduka-Nwosu

As a woman growing up in Nigeria, it is not uncommon to have it drummed in your head that Nigerian women are to be nurturers and active pursuants of corporate leadership careers and businesses.

In primary school, it is still not uncommon for children to be taught “roles of the father and mother” and to sing along to rhymes like: “Daddy in the parlour watching ball / Mummy in the kitchen cooking rice”.

It is not out of the ordinary for Civic and Social Studies textbooks to espouse that a woman’s ambition must stop at the altar of “supporting the father financially only where necessary”. Churches and other religious bodies also push the idea that a woman’s place is to be second fiddle to a man and that she must work to accomplish his dreams.

It is preached that a woman’s ambition must always be in service of a man, such that a “good wife” is one who hands her salary to her husband and never fails to remember that even as the breadwinner, she must always lower her voice and worth.

Women and ambition on a surface level seem to be a paradoxical pair in Nigeria. But how true is this?

It is imperative to ask this question in light of the rise of divine femininity preachers on social media apps like TikTok, who target younger women and encourage them to attack feminist women for fighting for the right to work. However, in Nigeria and other West African nations, women have always worked and contributed to the economic stability of communities.

Foluso Agbaje, a writer and financial analyst, wrote in her debut novel The Parlour Wife, about how market women in Lagos played a central role in stabilising the economic shifts and policies that came because of The Second World War.

In Igbo communities, it was recorded that the market was often seen as the preserve of women and the Aba Women’s War of 1929 against colonial taxation on women was funded and spearheaded by market women leaders.

So again: Why are younger Nigerian women actively ingesting divine femininity content and aspiring to rely on men when we have this history? Even more, what does ambition look like for the women who use social media to seek opportunities and can it be said that Nigerian women’s ambition has been stifled or never existed?

Furthermore, how does the conversation on Nigerian women’s ambition in an era of financial inflation address the challenges of women entrepreneurs in the area of seeking funding, loans and grants?

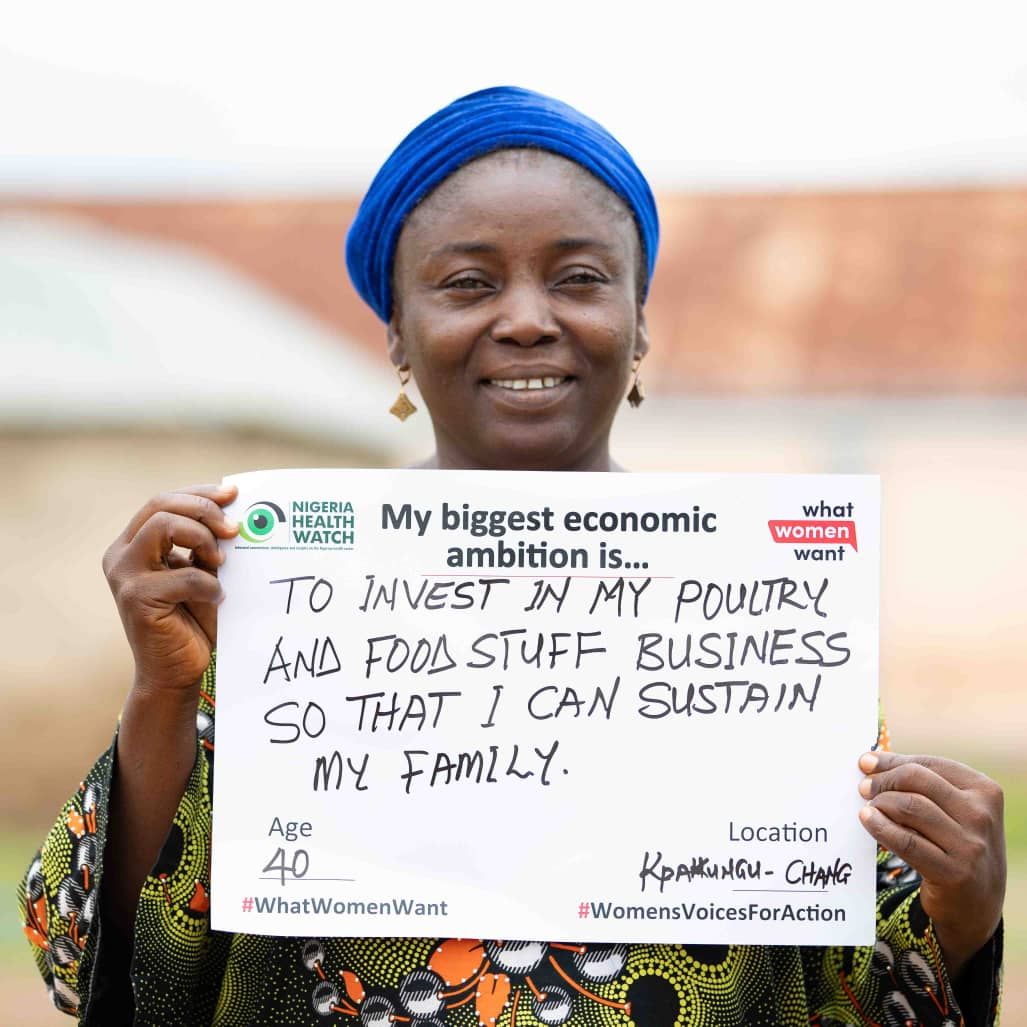

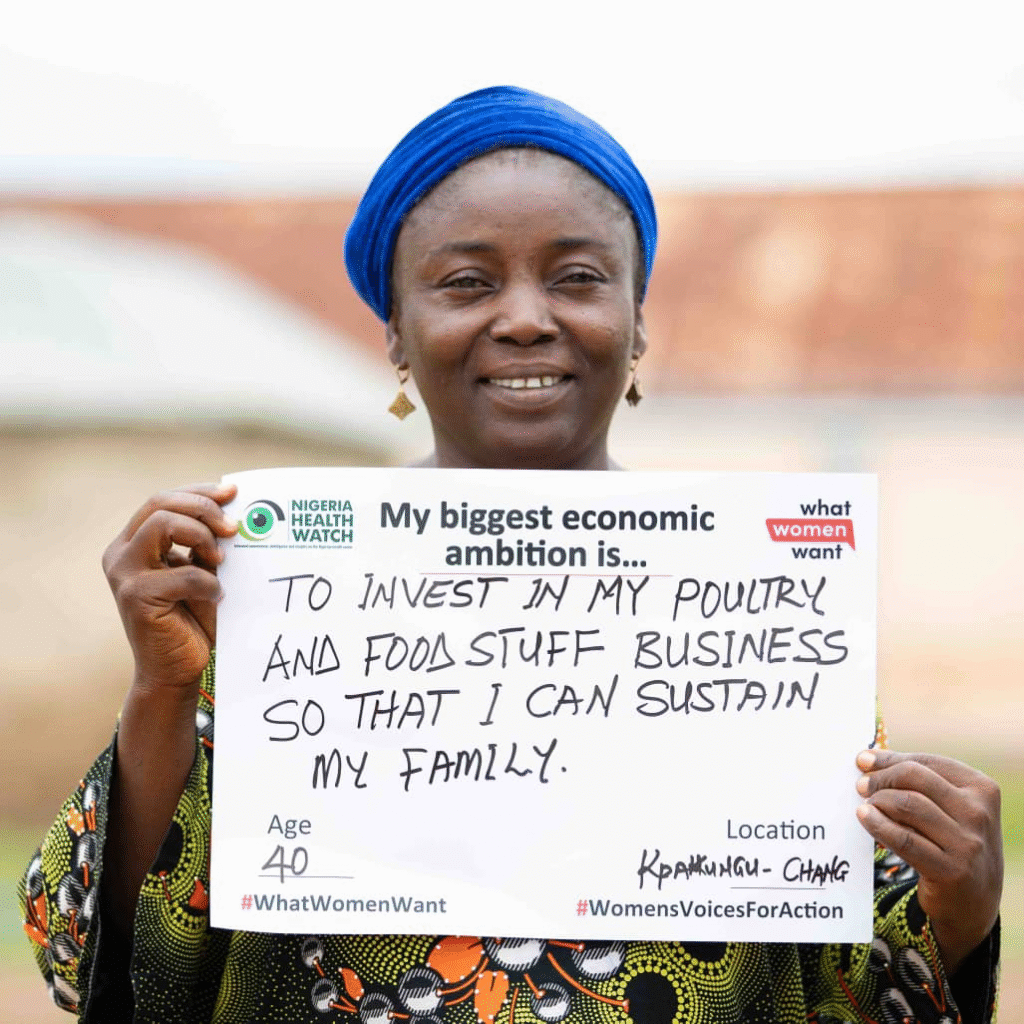

No other report adequately answers these questions, like the What Women Want report did. Conducted by organisations like The Gates Foundation, the What Women Want report is a survey of over 100,000 Nigerian women and Kenyan women aged 15-55+.

The survey aimed to capture the scope of women’s economic ambitions, the challenges behind fulfilling them and the areas of support needed by women in and out of businesses, corporate work and small/medium scale enterprises.

Contrary to the popularly held notion that gender roles in Nigeria means the man provides while the woman nurtures in the family, the report found that women in both Nigeria and Kenya expressed a strong desire to achieve financial independence.

The overarching desire for financial independence in both countries was so that they could adequately have the ability to cater not only for themselves but also for their families.

Concurrently, the desire for financial independence as a pathway for being able to take care of one’s family is in accordance with emerging conversations about the place of female breadwinners in a system that very often ignores the financial contributions of women and rather exposes them to violence.

Two articles came to mind when observing the patterns of the report. The first was an article on female breadwinners written by Glory Oviasuyi for Document Women.

In the report, one of the respondents based in Niger state, Nigeria stated that her biggest economic ambition is to be a banker.

However, she stated that the challenge for her had less to do with funding but more to do with the lack of family support and perception of female bankers in her community.

When presented with the statistic that 62% of the Nigerian women interviewed struggled with securing start-up capital, and equipment such that it played a significant barrier in their ability to successfully move ahead with businesses, an article published on Meeting of Minds UK about the need to give more women their credit for financial credit comes to mind.

In it, it was documented that the former Vice President of Nigeria Atiku Abubakar stated that in positive community building, he had realised that giving women loans was more beneficial to the growth of the community. He went on to state that in the past, he gave women loans and they often repaid on time while the men who were given loans hardly paid back and rather used the money to marry new wives.

However, access to funding is not the only area that sees a barrier for women entrepreneurs and other women’s ambitions in Nigeria and Kenya.

In Nigeria, between mid-July to October 2023, the report saw Nigeria Health Watch survey 100,000 women with an analysis of 102,758 open ended responses.

Based on the responses analysed, the ambition to open and expand a business took precedence for most women with 34% expressing the desire to start one when asked what their biggest economic ambitions were.

Of these women surveyed, when asked what was stopping them from realising their ambitions, while 62% stated access to funding options as a primary reason, another 7% stated that lack of proper education and training in the required field was a barrier.

Sometimes, access to funding is tied into educational barriers for the women profiled. For instance, an 18 year old woman in Kebbi State, Nigeria stated that her dream was to become a medical doctor but lack of funding to pay fees is what is preventing her from seeing it become a reality.

For her, the presence of a scholarship to pursue her educational needs is the best form of support for her ambition.

Other significant challenges included the ability to make a profit, jobs, and the time constraints that starting a business could have on family responsibilities.

Interesting to note is that women’s ambitions do not thin with age or become less fierce.

According to the report, women past age 30 are not less inclined to still be ambitious. The woman whose biggest ambition is to be a banker was 35 years old at the time of the survey.

Similarly, a 69 year old woman in Kebbi, Nigeria stated that her biggest economic ambition is to be a rice seller. She stated that the support she requires is funding to purchase more bags of rice as lack of money to purchase the bags is what is preventing her from seeing her dream actualised.

Regarding the areas of support needed to actualise the ambitions of Nigerian women as seen in the report, an overwhelming majority pointed to funding. This can look like scholarships, financial aid and access to low interest flexible loans.

Another area of support highlighted is the role of security and education in ensuring that their dreams are realised without the fear of insecurity issues. On a minor scale, some women pointed to the ability to acquire infrastructure like land especially if they are farmers or into real estate; some others also pointed to navigating government policies and being able to have access to facilities to address health concerns.

When asked to share her thoughts on Nigerian women’s ambition, Fifehan Osinkalu, founder of Eden Ventures, said: “While access to financial and digital resources is essential, it is not enough—true empowerment requires financial literacy, digital skills, and policies that meet women where they are.

We must move beyond inclusion to ownership, investment, and leadership, ensuring women not only participate in economies but also drive and shape them. This is about power, autonomy, and legacy—transforming families, communities, mindsets, and economies.”

It is important to note that women led businesses account for 37.1% of people in Nigeria’s informal economy with 90% of businesses in the informal economy making less than 500,000 naira profit monthly. Nigeria is home to approximately 40 million MSMEs, of which almost 90% are in the informal economy.

Even more important to note is that in 2023, less than 1% of the total approved national budget was allocated to WEE (Women’s Economic Empowerment) and associated projects.

As evidently seen, Nigerian women’s ambitions are not just a matter of advancing the personal goals of any woman.

Rather, by supporting the economic dreams of Nigerian women and providing access to funding, education, and security, the Nigerian economy would be better propelled towards more equitable economic success.