by Akinwande Jordan

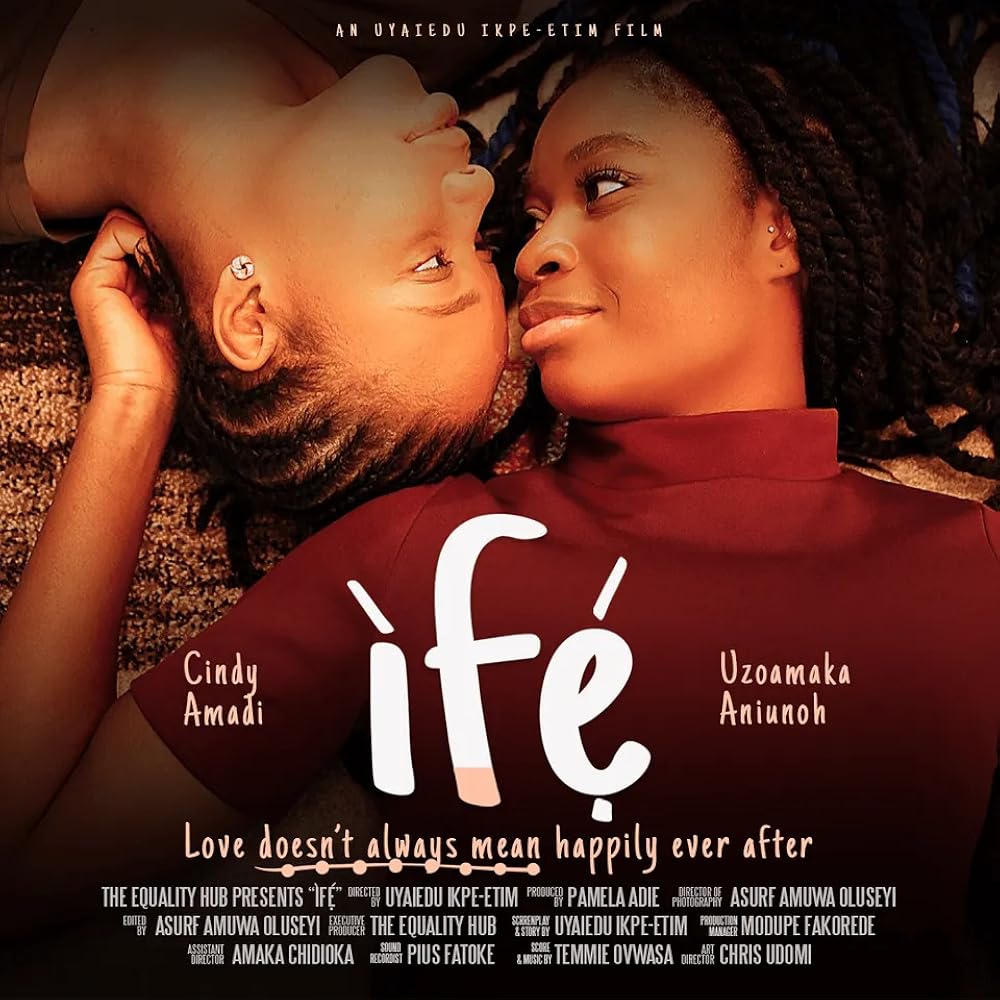

Every so often, an artwork arrives that is most radical not in its gesture, but in its stillness. Ìfé, a 38-minute film by Pamela Adie and Uyaide Ekpe-Etim, is one such work. It does not scandalise the state with overt slogans or staged protests. It does not set fire to the institution with gasoline. It simply dares to depict the normal —two women in love, in dialogue, in motion toward one another. In Nigeria, that is more than enough to cause institutional hysteria.

In Ìfé, Uzoamaka Aniunoh and the late Cindy Amadi share something more than ineffable chemistry—they share refusal. Refusal to over-perform, refusal to instruct, refusal to translate queerness into tragedy or pedagogical burden. Their intimacy is not aestheticised into spectacle. Nor is it hidden under metaphor. It just is. In a cinematic tradition that has made queer existence either invisible or unwatchable, this “just is” becomes a provocation.

One must begin here: the State detests nuance. Queerness rendered plainly, without moral framing, without external conflict, is unintelligible to a censorship regime that thrives on chaos and caricature. And so, Ìfé was banned before it was even released. But the ban—like most state attempts at moral gatekeeping—reveals more about the limits of authoritarian imagination than about the film itself.

Cinema in Nigeria has never been politically neutral, even when it pretends to be. The kinds of bodies permitted to desire, to fail, to survive are decisions made not merely by storytellers, but by the wider architecture of acceptable speech. Ìfé violates that architecture with alarming grace. It declines the nation’s obsession with queer morality plays and instead offers a picture of unremarkable love. Which, in a hyper-surveilled context, becomes its own act of resistance.

Let us be honest: we are no longer in the era of the closet as metaphor. We are in the era of erasure as an institution. And erasure is not the absence of presence. It is the domination of one kind of presence—straight, reproductive, and state-sanctioned. Pathological heteronormative. The “official image” of Nigeria does not include a woman looking longingly at another woman. The image must be edited, censored, or buried. But Ìfé refuses this fetid logic. It insists that to depict queer Nigerians is not merely to include them—it is to confront a social contract built on curated fictions.

Here, it is necessary to revisit a truth Susan Sontag understood: style is not decoration; it is politics. Ìfé does not rely on narrative excess. It does not signal its relevance by exaggerating the suffering of its subjects. This restraint is its defiance. It gives us quiet, not as a void, but as form, not as aesthetic detachment, but as resistance to the state’s expectation that all queerness must justify its existence through trauma.

We are inundated with stories that offer gay characters as either victims or clowns. The effect is not mere fatigue, but aesthetic claustrophobia. The audience begins to internalise a template in which queer lives must always be disrupted by death or humiliation. Ìfé dismantles this not through political rhetoric, but through cinematic tone. The film’s pacing, the ambient silences, the absence of an antagonistic plot—all of these gestures toward a cinema of trust. It trusts the audience to witness without judgment. It trusts the characters to exist without performance.

But we must not mistake this restraint for naivety. Ìfé is aware of its risk. The performances are deeply calibrated. Uzoamaka Aniunoh, in particular, plays her role with a kind of fatigue and less emotional exhaustion than historical awareness. Her character is not surprised by the fragility of desire in a hostile landscape. She moves through the narrative like someone accustomed to forceful deletion, and yet determined to be legible, if only to herself. There is dignity in that.

It is tempting to speak of films like Ìfé in terms of representation, as if visibility alone constitutes liberation. But visibility is not a neutral good. What matters is how we are seen, who is doing the seeing, and to what end. Ìfé refuses the politics of begging to be understood. It does not try to make queerness digestible for a hostile audience. It insists on opacity, on inside jokes, on private languages. It does not aspire to universalism. And this, precisely, is what makes it valuable.

Queer cinema should not aspire to reproduce the narrative patterns of straight cinema with reversed pronouns. It should interrogate structure. It should challenge whose pain is allowed to be tender and whose joy is allowed to be mundane. The work of queer cinema is not merely to reflect life but to expand the grammar of what is sayable, and what is survivable. Ìfé is an imperfect but essential contribution to that grammar.

There is no queer cinema in Nigeria without consequence. To direct, to act, to fund, to share a film like Ìfé is to participate in an underground circuit of cultural insurgency. Every download is an act of defiance. Every screening, a risk. That we have to smuggle intimacy through Telegram and Google Drive links is itself a symptom of the wider absurdity—that love between women is a file marked “NSFW.”

Yet even under these conditions, the film exists. And that existence is an indictment. Not of Nollywood’s silence—although that too—but of the public’s willingness to pretend that absence is a form of peace.

The task now is not merely to applaud Ìfé, but to demand its multiplication. We need films that are not about queerness, but from queerness. We need melodramas, thrillers, comedies, all operating within the logic of lives not built around heterosexuality. We need mess. We need excess. We need failure. Not every queer film must be a manifesto. Some must be reckless and dionysian. Some must be boring. But all must insist on presence.

That is the legacy of Ìfé. Not that it is the first. But that it makes a second possible.

Let us end here: the image of two women in love is not dangerous. What is dangerous is a nation so terrified of such an image that it would rather kill the archive than allow it to grow.

But archives, like desire, are persistent. They survive in fragments. They whisper across firewalls. They wait in flash drives, mislabeled. And someday, some queer teenager in Ilorin or Nsukka or Abeokuta will find Ìfé, and it will feel less like discovery than confirmation