by Akinwande Jordan.

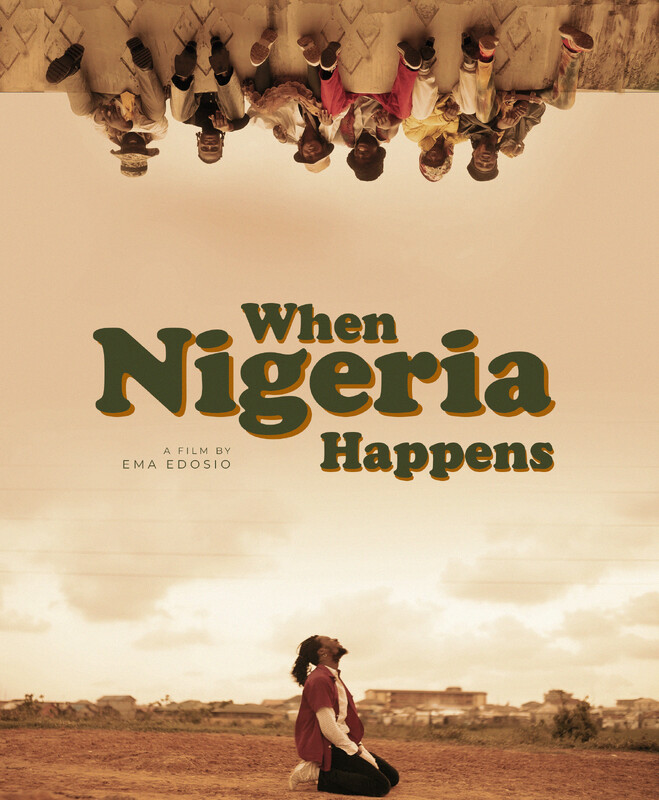

Every single frame in Ema Edosio’s When Nigeria Happens doesn’t ask for your tears—it dances them out of you in full force. Not through melodrama or sentimental string music, but through movement: a twitch of despair, a stumble into grace, a quiet refusal to collapse. It’s the moment you realize you’re not watching filler art—you’re watching something choreographed with the rigor of theatre and the abandonment of ineffectual realism.

Edosio, whose earlier work Kasala! flirted with kinetic chaos—where she depicted the unfiltered realities of Lagos without apologies—seems drawn to stories on the margins. The plight of the unfortunate isn’t just a subject; it’s her staging ground. Here, she finds a far subtler rhythm alongside the gorgeous choreography of Qudus Onikeku, like a stripped-down monologue performed on an empty stage.

Her camera is no longer omniscient—it is a weary witness. This is not Nollywood-as-spectacle. It is Nollywood as endurance art. And in many ways, it’s Samuel Beckett. It’s Ola Balogun. It’s also uniquely Edosio.

When Nigeria Happens tells the story of six young dancers—Fagbo, Pocco, Lighter, Movement, Colos, and Poppy—who move through life with fire in their feet and defiance in their hearts. Dance is their escape, their rebellion, their small corner of freedom in a country that often asks too much and gives too little. But everything shifts when Fagbo’s mother falls seriously ill. Suddenly, the cost of staying afloat becomes real and heavy. As Fagbo scrambles to find money, their tight bond begins to stretch. Love, loyalty, and ambition are pulled in every direction.

Dance here is not spectacle—it is muscle memory, protest, and prayer. The bodies we watch on screen do not perform; they testify. In a country where language is often met with dismissal, the body becomes an archive and an argument. And every gesture contains residue: the weight of the past, the stubbornness of hope.

This isn’t poverty porn. Nor is it a neoliberal fable of resilience. Edosio sidesteps both temptations. Instead, she builds a cinematic stage where movement is its own argument. Each dancer walks, runs, waits, limps, crawls. Each gesture becomes a syntax of struggle, like a dancer interpreting an unscored symphony. There is no sentimental uplift—only choreography carved from necessity.

Even the stillness is choreographed. In several scenes, Edosio allows the camera to linger on moments of breath, of exhausted poise, where it seems the characters are suspended between collapse and continuation. These moments feel almost balletic in their composition—an act of holding one’s ground as an act of grace.

Minimalist in style but not in substance, When Nigeria Happens lingers in what others might cut. Lagos becomes a chorus of muted tragedies and fleeting joys. The city breathes not as backdrop but as antagonist, crowding the frame and the soul. Edosio’s Lagos is not a canvas for aspiration—it is an obstacle course.

One might say, channeling Artaud, that Edosio is trying to “shock us into seeing.” But hers is not the scream of madness; her screams mirror resilience, mirroring what it takes to exist in a country that is constantly cannibalising itself. There are no stylized breakdowns here, no grandstanding speeches. Just the quiet refusal to be undone.

The cinematography leans deliberately toward restraint. No saturated lighting or dolly shots to dazzle the audience into complacency. What we get is composition-as-confession. You feel the constraints not as metaphor but as lived geometry: cramped apartments, overpopulated rehearsal spaces, endless queues. The mise-en-scène performs anxiety with the clarity of a dancer extending her limbs just to show how little room she has to move.

Throughout the film, one senses a deep reverence for the embodied act. Every pirouette in the face of poverty, every pop-lock timed against power cuts, feels like it is being performed not just to survive—but to insist. The dancers’ bodies become fugitive texts, smuggling meaning into a world that is deaf to spoken pain.

The theatricality of it all is unmistakable. Each performer seems to be auditioning for an invisible director, their movements freighted with unspoken soliloquies. There’s a sense that everyone is mid-monologue, even when silent—especially when silent. The drama isn’t external; it’s anatomical.

And it’s not just the domestic sphere that Edosio critiques. The larger institutional rot—the broken healthcare system, the informal labour market, the daily petty humiliations of life in a “developing” nation—is presented without editorialising. It’s just there. And because it is simply there, we feel its weight all the more.

The film’s inclusion at the 2025 Locarno Film Festival—where it has been slated as the opening film in the “Open Doors: Opening Worlds” section—feels entirely appropriate. That section champions bold, emerging voices. And what Edosio brings to the international stage is not just boldness, but conviction: a belief that local suffering can be rendered with global precision. When Nigeria Happens didn’t merely represent Nigerian cinema; it challenged the festival audience to see dignity not in spite of hardship, but through it.

What makes When Nigeria Happens linger isn’t its story alone—it’s the rhythm of it, the careful cadence, the refusal to resolve. In a world of short attention spans, Edosio stages something closer to butoh than blockbuster: slow, deliberate, filled with tension and beauty that demands your patience. It’s the kind of film where a footstep can be an elegy.

If there’s a critique, it lies in the film’s risk of monotony. Edosio occasionally lingers too long on the same visual or emotional beat, as though doubting whether we’ve felt it deeply enough. But that, too, echoes the life it portrays: Nigerian survival often feels like waiting for a relief that never comes.

So, When Nigeria Happens does not offer escape, resolution, or revenge. What it offers is something harder to dramatize: the poetics of persistence. When Nigeria Happens is a quiet resistance film. A barefoot theatre of the everyday. A cinema that invites not applause, but reckoning. And that’s what Edosio has achieved—a slow, searing dance for those who have no stage, no net, but still perform.

Until the dance stops.

But it never does.