By Philemon Jacob

The “Afrobeats to the World” movement has yielded undeniable success. Nigerian artists are now international sensations, selling out arenas, scoring Billboard Hot 100 hits, and winning Grammys. Milestones that seemed out of reach two decades ago are now within arm’s length for the average breakout artist.

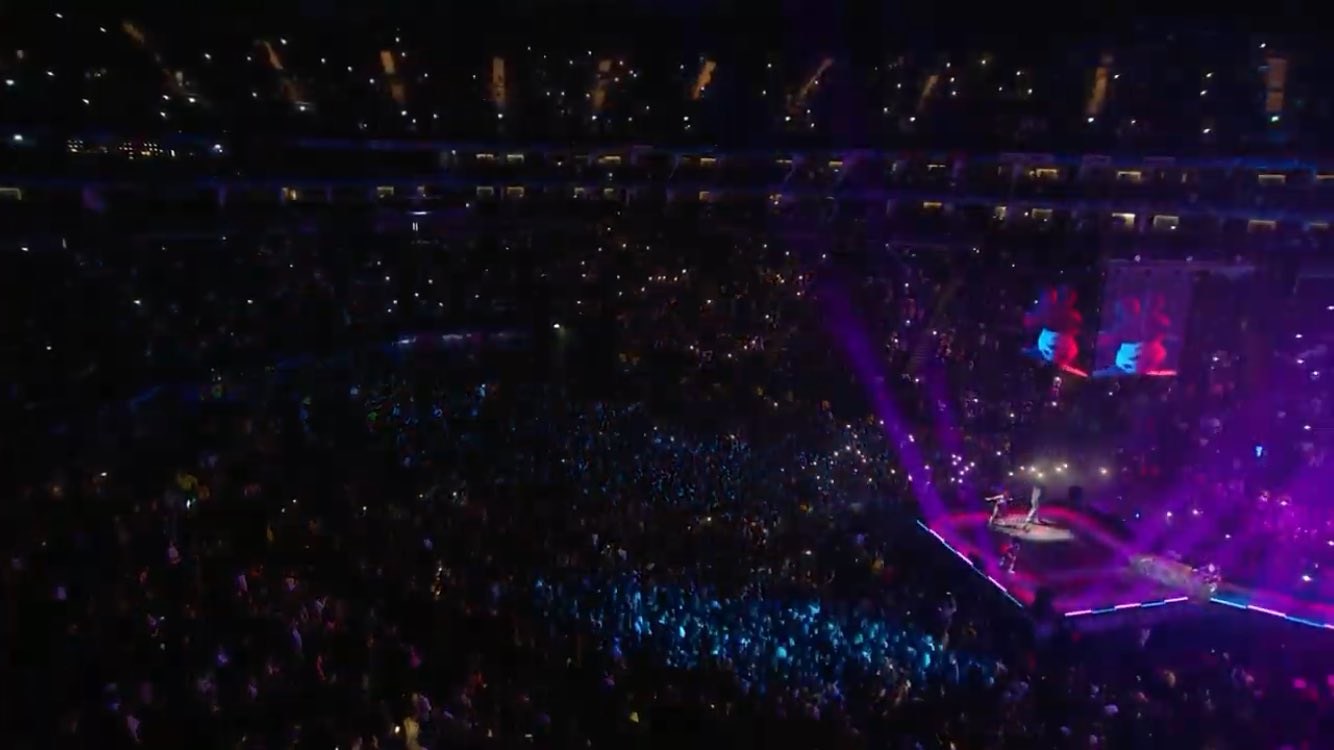

The genre that blossomed from the streets of Lagos has truly gone global. Asake, for instance, is an artist who sings predominantly in Yoruba yet commands the unwavering attention of massive audiences in cities like New York (Barclays Centre), London (The O2 Arena), and Toronto (Scotiabank Arena).

However, for some, that success may have come at a cost.

In a recent interview on Channels TV’s Rubbin’ Minds, legendary Nigerian producer ID Cabasa voiced his concerns about Nigerian artists losing their cultural identity in the pursuit of international validation. While he acknowledged the positives of the attention Afrobeats is receiving, he didn’t mince words about the trade-offs, boldly saying Afrobeats now sounds more like R&B.

The DNA of Afrobeats borrows a lot from American music genres. The likes of 2Baba, Paul Play, and P-Square blended Western R&B music with Nigerian percussive arrangements and local languages. A recent Spotify report titled Journey to a Billion Streams even emphasised this, pointing out that the genre’s growth has been driven by “genre-blending, experimenting with Reggae, Amapiano, R&B, and more.” That adaptability is what makes Afrobeats globally appealing.

However, some changes in Afrobeats may offer some validity to ID Cabasa’s argument. One of the most noticeable changes in Afrobeats over the years is the tempo. In the 2000s and 2010s, the genre thrived on high-energy, fast-paced beats. Songs like Wizkid’s Pakurumo, P-Square’s Alingo, Davido’s Dami Duro, and Dr Sid’s Pop Something were driven by vibrant percussion that ignited dancefloors. A reflection of Nigeria’s bustling energy and party culture. Back then, Afrobeats was kinetic, and the music moved bodies before anything else.

But as the “Afrobeats to the World” movement began to pick up steam around 2018–2019, the tempo took a subtle dip. Suddenly, mid-tempo records became dominant, and songs became more laid-back, moody, and atmospheric. The focus slowly shifted from frenetic dance records.

It’s also important to note that around this time, the market shifted from a singles-driven model to an album-focused one. In the singles era, fast-paced, radio-friendly records designed for instant impact were the norm. But as albums became the dominant format, Nigerian artists had to readjust, prioritising mid-tempo records that could seamlessly fit into a body of work and still hold potential as a single. An album filled with high-octane, fast-paced tracks can feel scatterbrained, while a collection of mid-tempo songs often offers a more fluid and cohesive listening experience.

Mid-tempo records also seem to translate better across borders, as they’re easier to mix into international playlists and more suitable for chill listening. They also align with Western R&B and pop pacing, which is why it’s no surprise that many of Afrobeats’ biggest global hits, such as Wizkid’s Essence, CKay’s Love Nwantiti, Rema’s Calm Down, and Oxlade’s KU LO SA, are carried by melody and emotion rather than rhythm and percussion.

Beyond tempo, the very language of Afrobeats has changed. In the early to mid-2010s, lamba (code name for Afro-pop) was central to the genre’s appeal. Artists like Tekno, Olamide, Zlatan, and Naira Marley made music with lyrics that vibrated with the language of the streets. The lyrics were spontaneous, scatterbrained, local, and rooted in Nigerian culture. Even when the production leaned towards Western influences, the lamba gave it cultural weight.

In recent years, there’s been a shift toward more articulate and expressive songwriting. Verses that are cleaner, clearer, and more emotionally expressive. The themes still revolve around universal topics like love, sex, heartbreak, personal evolution, and motivation, often delivered in English or pidgin. These factors being considered seem to indicate a drifting away from the vibrant core that once defined Afrobeats.

The question then is, should we be worried about Afrobeats losing its cultural essence in a bid to appeal to its international consumers?

Here are my thoughts.

To say Afrobeats is losing its essence is to say the genre is static. But Afrobeats, like any genre that exists, is defined by context, audience, and time. The version of Afrobeats that dominated the 2010s was built for that era. Club-ready, rhythm-heavy, and soaked in street lamba. However, the audience has grown, and it is natural for the sound to reflect those changes.

This generation of Nigerian artists didn’t just wake up trying to appeal to international audiences; they are also a product of what they grew up listening to. Many of today’s stars were raised on 2000s R&B, hip-hop, and pop. Artists like Usher, Chris Brown, 50 Cent, Beyoncé, Akon, and Lil Wayne were household names in Nigeria during their childhood. This upbringing created a generation of Nigerian musicians whose taste was already influenced by the West even before they began making music.

This is completely different from the older generation of Nigerian artists who were influenced by local genres like Fuji, Juju, Highlife, and Afrobeat in the mould of Fela Kuti.

It is also important to understand that today’s listeners are more exposed than ever to a wide range of music across genres and cultures. With streaming platforms and social media, Nigerian fans have developed a more refined and diverse musical palate. This acquired taste has raised expectations around the production and songwriting. Artists now have to meet the standards of a generation that’s grown up on everything from Afrobeats to trap, alté, K-pop, and UK rap – everything.

And the idea that Afrobeats is losing its core doesn’t hold water when you look closer. Rema’s Heis won Album of the Year in 2024. It’s an album packed with experimental sounds that are still rooted in African rhythms and lamba. Ozeba was a unifier, a Street-Hop song by a global superstar with fans around the world and across every demographic of Nigerian music listeners. From alté to diaspora to Ibile, everyone vibed to it. Shallipopi’s 2023 run was defined by catchy, high-energy Amapiano records rich in Benin cultural references and street lingo.

So while Afrobeats may sound slower or cleaner, it’s not because the culture is being eroded. It’s because the music has evolved, and the audience is much bigger than it used to be. The artists have a much wider audience to cater to, and they are tailoring their music to a wider audience while staying in touch with their home base.

What we’re witnessing is Afrobeats on its own terms, evolving while still grounded in its roots. The tempo might have slowed, the lamba might be less frequent, but the pulse of the culture is still loud and clear.