By Akinwande Jordan

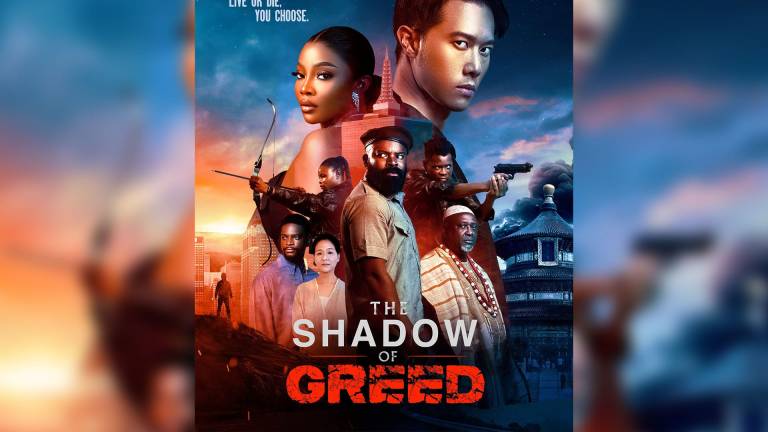

Akay Mason’s The Shadow of Greed is a film that wants to do everything at once. It reaches for the political, the spiritual, the allegorical, and even the international. It wants to be Lord of the Rings. It wants to be Michael Mann’s The Insider (1999). It wants to be Breaking Bad. It wants to be any Jason Statham flick that comes to mind.

Directed by Akay Mason and produced by Tim McManus, it carries the burden of ambition—and not always gracefully. Its heart is in the right place: corruption, performative leadership, international exploitation, spiritual warfare—these are heavy, urgent subjects. And to its credit, the film doesn’t shy away from them. But somewhere between intention and execution, it stumbles.

The story is set in the fictional Nigerian town of Ajaka, where Oba Adebukola Adele, played by Toke Makinwa, rules with charm and menace. In public, she presents herself as a woman of the people, draped in modesty, speaking the language of shared struggle. In private, she is siphoning money from a Chinese-funded infrastructure project intended to uplift her community. This split performance—humility as costume, corruption as ritual—is the foundation on which the film builds its critique. The Oba is not just a character; she is a stand-in for generations of Nigerian leadership that thrives on spectacle while starving the people of substance.

Her foil is Jerry Chen (Kent S. Leung), the project’s Chinese coordinator. Jerry Chen is ethical, professional, and unflinchingly committed to the task at hand. The moment he begins to question the Oba’s dealings, the power struggle intensifies. What follows is a series of escalating maneuvers—manipulation, seduction, smear campaigns, even physical threats—as both characters attempt to assert control. The conflict is clear, the stakes are grounded, and the setup is ripe for a tense political drama. But the film doesn’t stop there.

Where The Shadow of Greed attempts to stand apart is in its spiritual dimension. Beneath the battle over money and influence lies another, deeper war—one rooted in mysticism and cultural belief systems. There’s a supernatural energy pulsing beneath the surface, with visualizations of spiritual entities, rituals, and metaphysical confrontations that bring Nigerian and Chinese traditions into visual conversation.

It’s an ambitious gamble, and in its best moments, it adds texture. The CGI is surprisingly competent—especially in one sequence involving a Chinese dragon—but elsewhere, the visual effects struggle to hold up against the weight of the story. It’s not the scale that’s the issue, but the uneven tone: the shifts between the physical and the spiritual often come without warning, making it hard to remain grounded in either.

The film’s pacing also suffers. At over two hours long, it feels overextended. Scenes that should move briskly linger too long. Dialogue is often overly expository, spelling out what could be conveyed with silence or subtext. We’re told how to feel, what to think, and what the stakes are—again and again—until the weight of the repetition dulls any emotional sharpness. The script has something important to say, but it rarely trusts the audience enough to say it with restraint.

The performances, like the storytelling, are a mixed bag. Toke Makinwa commits to the role of Oba Adebukola with confidence, but the character lacks the layers needed to elevate her beyond a trope. There are glimpses of nuance—a quiet glance, a pause before a lie—but they’re buried beneath monologues that reduce her to a pantomime villain. She’s supposed to be both terrifying and seductive, but ends up feeling like a character from a cautionary folktale. Kent Leung plays Jerry Chen with quiet resolve, but the script doesn’t allow him much beyond being the incorruptible outsider. He is less a character than a symbol of order, of modernity, of ethical governance.

It’s Gabriel Afolayan, playing Castro, who provides the film with some much-needed depth. His performance is raw, believable, and grounded in a kind of moral confusion that feels true to life. Castro is a man trapped in a system he didn’t design, trying to survive without entirely surrendering his soul. His scenes offer brief flashes of what the film might have been, had it stayed closer to the ground. Olumide Oworu also deserves credit for a quieter, more internalised performance, bringing emotional gravity to a role that could’ve easily been forgotten.

On a technical level, the film has moments of clarity. The cinematography—especially the handheld sequences—manages to convey tension in ways the dialogue often fails to. There’s an intimacy to some of the framing that works well for a story so rooted in deception and double-speak. But these moments are often disrupted by choppy editing and inconsistent sound design. In particular, scenes that are meant to feel urgent are dragged down by slow cuts and clunky transitions. There’s a clear desire to craft atmosphere, but the tools sometimes get in the way of the tone.

More concerning than any of this, though, is a factual error that stands out sharply: the film depicts a hospital refusing to treat a gunshot victim without a police report—a policy that was repealed in Nigeria several years ago. In a country where misinformation can literally cost lives, this is more than a script oversight. It risks reinforcing a dangerous myth, especially when the scene in question is framed to deliver a dramatic emotional punch. For a film so clearly invested in exposing systemic failure, this moment feels ironically irresponsible.

Still, The Shadow of Greed is not without merit. Its central ideas—about how power is performed, about the way corruption clings to cultural authority, about the hollow theatre of public service—are timely and urgent. The film is at its most compelling when it lets those ideas breathe. When it pauses to show the quiet grief of citizens forgotten by progress, or the tension in a loyal aide’s hesitation before carrying out an immoral order, it captures something real. Something sad and familiar.

The film also deserves some praise for attempting to widen the lens of Nollywood. There is a global ambition here—one that seeks to push beyond local clichés and open up new narrative possibilities. That the film falters in delivering on that ambition doesn’t make the effort any less important. This isn’t just Nollywood retelling another moral fable; it’s a film that wants to be in conversation with international cinema. It doesn’t always know how, but it’s reaching for something more, and that matters.

What holds The Shadow of Greed back is its inability to focus. It tries to do too much at once, and in doing so, stretches itself thin. It wants to be poetic and political, supernatural and realistic, theatrical and restrained. In trying to juggle all of that, it loses the very intimacy that would make its message land. What we get is a film filled with sound and symbols, but not always enough silence or space.

And yet, for all its flaws, it leaves an impression. Maybe not in the way it intended, but in the way ambitious, messy art sometimes does. You don’t forget it, even if you spend the ride home picking it apart. Because at the centre of all its excess is a truth many Nigerians know too well: that power often hides in plain sight, wrapped in tradition, shielded by faith, and justified by performance.