by Angel Nduka-Nwosu

There are books that make you remember other books fondly. There are books that seem like time capsules which exist to transport you to feelings of nostalgia.

There are books that come in as timely and almost coincidental reminders that the fight for women’s freedom is far from over in Nigeria. There are books that tear you apart and still ensure to leave you brimming with the awareness that the only way to happiness as a woman is if you intentionally define for yourself a path free of caring what people will say, think or do.

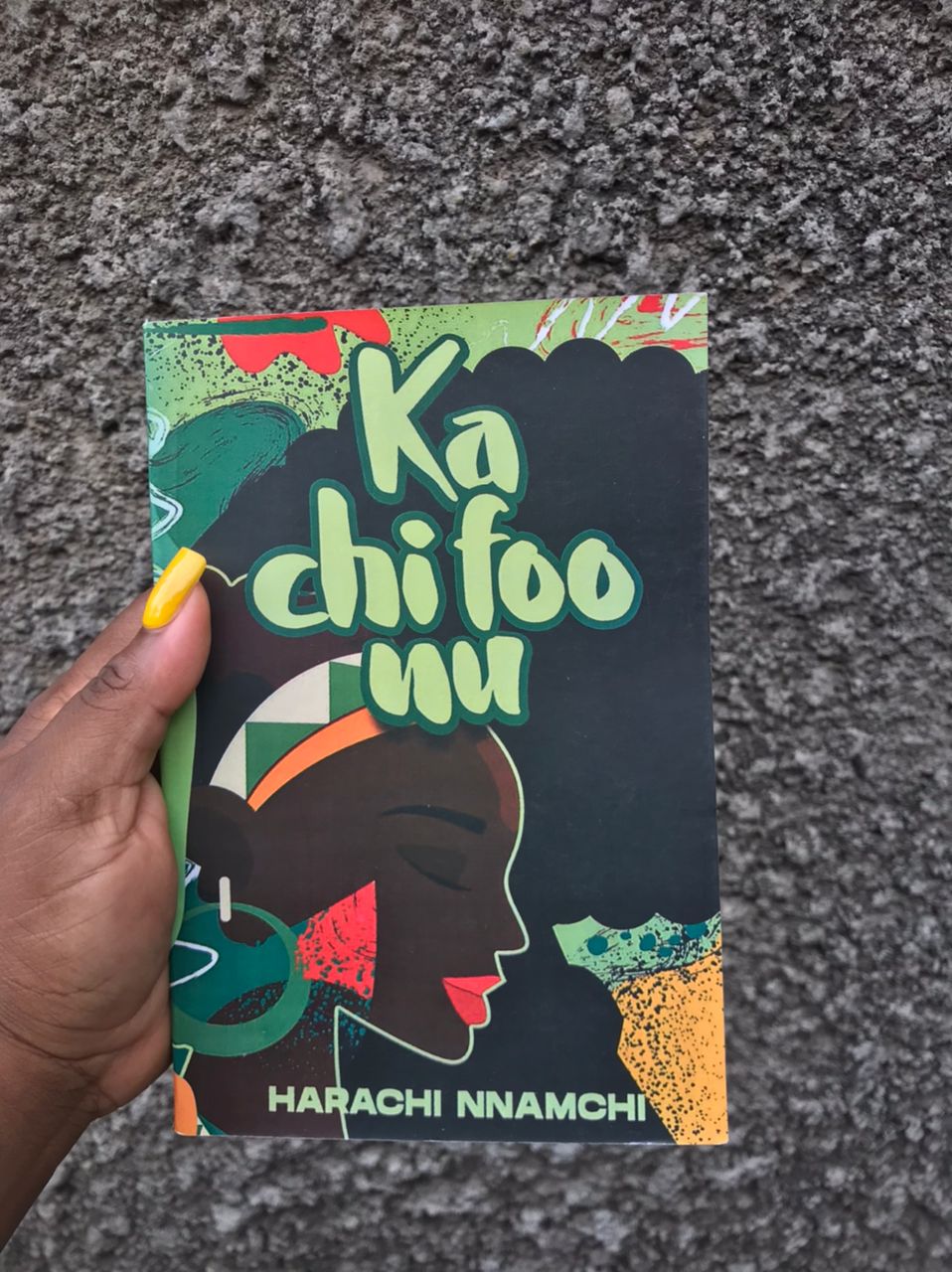

Harachi Nnamchi’s short story collection titled Ka Chi Foo Nu elegantly evokes all emotions, nuances and feelings described above. For one, it is a collection that reminds me of books like The Thing Around Your Neck by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Better Never Than Late by Chika Unigwe.

Made of five stories and published by Gemspread Publishing, the bulk of the stories are set in Eastern Nigeria in towns like Nsukka. At the core of the collection is the exploration of what it means to be Igbo, woman and the search for self development in situations that state that being a wife and mother is women’s defining glory.

The collection starts with a story written in an epistolary manner. In it, a woman explains in detail to her long time friend how her rich husband’s philandering ways has seen her struggle with sexually transmitted diseases. This story is timely because in recent times on social media, there has been a discourse on if it is acceptable to leave a cheating man if he is rich and a provider. Through the use of stark imagery, the story lets us know that asides the emotional damage that can come from being cheated on, women who stay back with cheating men are at risk of losing their lives to untreated sexually transmitted diseases.

If one observes Nigerian women’s literature, a running theme is the effect of sexual and gender based violence on women’s sense of self. Novels like Tomorrow I Become A Woman by Aiwanose Odafen particularly paint how patriarchal mothers continually ensure that women stay on in situations that are near death experiences. Following in that tradition, the second story in the collection adds a twist to gender based violence. It documents how a mother’s willing negligence affects her daughter’s ability to stand up for herself and creates in her daughter negative mental health experiences.

Harachi Nnamchi is a screenwriter, mother and owner of a food business called Nri Oma. The diversity of her exploits and her dedication to women’s self development shows itself in this collection. In all the stories, one observes that there is the constant reminder to women that we must give ourselves the permission to start over and explore all the parts of us that demand to be brought to life.

As an Igbo woman raised in Lagos, I particularly loved Ka Chi Foo Nu due to how it widens the scope of literature about Igbo people. Stories about Lagos are important but one has to admit that there seems to be a dearth in literature that explores other Nigerian cities.

Ms. Nnamchi follows the pattern of writers like Chika Unigwe who is a writer intentional on exploring the lives of Nigerians in cities and towns like Jos, Abuja, Calabar, Nsukka and places in the North of Nigeria like Kano and Kaduna.

This collection of stories explores life in Lagos yes. However, the lives of women in lesser explored Igbo cities were given the spotlight and that was interesting to observe as an Igbo woman. It showed me that though women share things in common, the environment we grow up in still provides unique challenges that must be spoken about.

A very remarkable thing in this collection is the manner in which it raised themes that tend to be overlooked or hurriedly swept under the carpet in contemporary Nigerian society. Three of those themes are queerness, the poor treatment of domestic workers and the negative treatment of women by Catholic priests.

In the first story, we see the dilemma of a mother who wants her daughter to love her roots but also acknowledges that her daughter’s queerness and same sex attraction makes her a target for homophobic violence. This realisation comes to her after witnessing violence being given to a queer man. What I loved about this part of the story is how it centered the struggles of queer women from a mother-daughter perspective.

Too often in Nigerian literature, we do not see or hear queerness spoken about in terms of a parent wanting to protect their child. While the reality indeed is one where older parents are more likely to turn away queer children, reading this was a reminder that even in older generations, there exist outliers who will stand by their children no matter what the consequences may be.

Although conversations exist on the gendered angles and abuse faced by domestic workers in Nigeria, the issue of the abuse encountered by women and underaged helps is not as amplified as it should be. In the collection, Ms. Nnamchi follows the tradition of novels like The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives when she highlights how female housekeepers encounter abuse and have hardly anyone to turn to.

The collection also speaks on the lives of daughters and “illegitimate” children born to Catholic priests who groomed their mothers. It is a reminder that sometimes the origin of traumatic behaviour in women and how they relate to romantic partners can only be traced and resolved when they undo the shame behind how they were conceived.

The hallmark of a good book is if the topics it addresses can stand the test of time.

What stands out Ka Chi Foo Nu is that it not only honors the women who have lost their lives and personhoods to the vagaries of patriarchal dictates, it also provides a template that assures women that to live fully is to give back praise to the women who were not so lucky.

It is to remember that a life outside of sexist commands is the only way to soothe the memories of our sisters and foremothers who had no choice but to obey those commands.

For that, I praise and honor Harachi Nnamchi for writing this timely collection of stories.

Related: