by Akinwande Remilekun

At the throbbing core of the African film scene lies an absence. The absence of a genre that is, without exaggerating, essential to a person’s formative years – the coming-of-age genre; a mass media staple that has somehow eluded the mainstream landscape of African and specifically Nigerian films. We have placed cinema addressing the angst of the youth into an obscure place, and there’s a need to look at why and how we can make it important in our part of the world.

In genre studies, coming-of-age can be defined as any mass media, be it theatre, film, television or video games, that focuses on the growth of a young protagonist and how they transition into adulthood. Simply put, the stories about preteens, teenagers and, as of late – young adults and how they navigate what comes with those stages in life. To the average (read as suburban, middle-class Nigerian with Internet access), the coming-of-age genre is an American idea only to be seen through the lens of the American perspective. Our bookstores and film folders are filled with John Hughes films, John Green books and the John Green adaptation. We may or do not need our own equivalence of films like Pretty In Pink, Dazed And Confused, The Fault In Our Stars etc., but there’s a lack of film that makes young people feel personally addressed.

When people think of coming-of-age media in Nigeria, they think of MTV’s Shuga, which found its way here after gaining popularity in East Africa – or they think of Netflix’s Far from Home, which although can be seen as a worthy attempt, still has the conspicuous flaw of leaning into the American perspective of youthful media/cinema. There’s little to nothing about the reality of things here. But that’s almost a fault we can’t pin on anyone; American media are our most immediate reference points for anything imitated and consumed beyond our borders.

To write a coming-of-age story for the Nigerian audience, one has to do away with appeasing the upper class – the Lekki elites and Victoria Island youths, the collective-minded crowd searching for something void of trauma or life-altering conflict. To be generally young is like skydiving every day without a parachute. To be a young person in Nigeria is to skydive every day from a burning plane without a parachute – it’s a different dynamic from the John Hughes pictures and the John Green adaptation. It’s an unholy mixture of growing pains and generational misinformation on what it means to be young. And there’s undoubtedly an audience for such stories, a large one at that.

The most recurring critique of Netflix’s Far From Home was “it’s not relatable” – translation; this is the experience of a few posing as the experience of all. And although relatable art doesn’t equate to good art, there’s still a joy in that commonality we all have in something that makes us feel personally addressed.

The loud absence is not a cinematic state of emergency, but it’s loud enough to be noticed. It might be more difficult to make films of this nature now due to the ubiquity of streamers and the lack of funding for any art that doesn’t come off as patriotic or politically rebellious, but the making of a decent but serious film for a younger demographic is in and of itself rebellious against the very nature of complacency. It’s rebellious against the noise that makes the voice of ordinary young people inaudible.

According to Harper’s Bazaar: ‘The appetite for the genre is ever-growing since it allows viewers to relive their teens with all the retrospective wisdom and none of the existential angst”- it’s becoming a global phenomenon that perhaps gained a resurgence during COVID among a lot of young adults across the globe, but for us, there’s no major representation there, nothing to embellish our legitimate angst and stifled anger. Nothing to tell our stories. There are countless stories to be told about innumerable experiences, stories not tainted by the earlier mentioned American perspective.

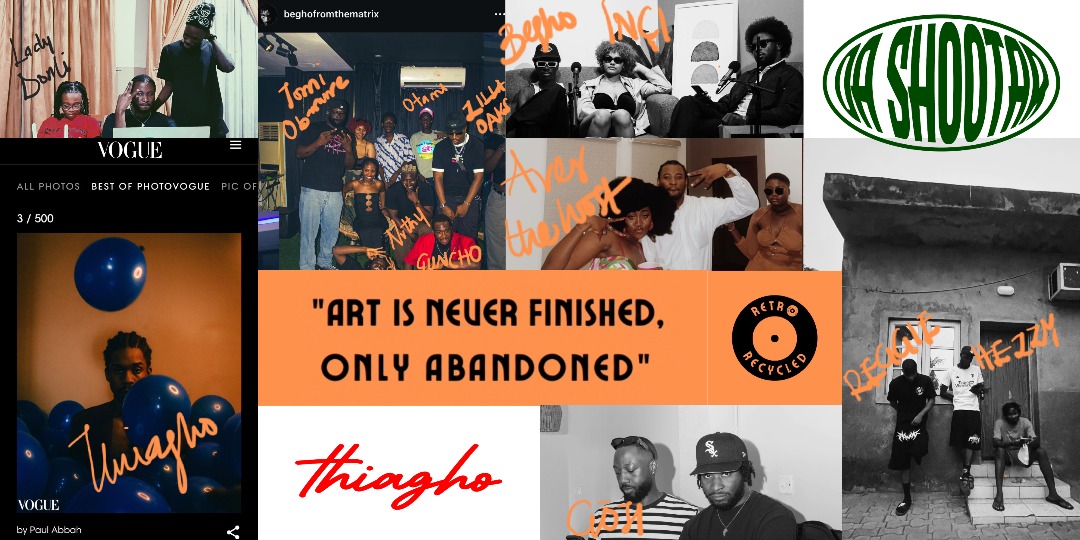

Once our filmmakers and writers can figure that out, we might have some of our most decent pieces of cinema in the last decade. We have the music, we have the talent, we have the esoteric pop culture, we have the absurd fashion eras, and we have the stories. There’s an abundance of material in the literary world waiting to be adapted; writers like TJ Benson, Akwaeke Emezi and Leslie Arimah Nnena have flourished in that genre whilst telling serious stories. We as people will never be young again, but the youthful cinema lives up to its name – it stays forever.