by Akinwande Jordan

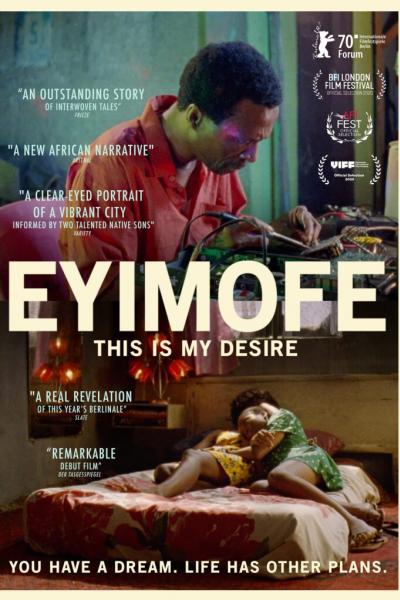

Beneath the airplane-filled skies, the edifices on familiar terrain and estates of luxury, all buzzing with the flight of engines. Amongst the pulsating disunity of Lagos city, past all the traffic and clusters of businesses, deep into the hanging slums of Ikeja; The Esiri brothers puts us in the enormous presence of the known with the first shots in Eyimofe (This Is My Desire) — an entanglement of cables and a factory worker by the name of Mofe (Jude Akuwudike) who is called upon to fix a medley of malfunctions. He proffers solutions, he tweaks like a meticulous mad scientist despite the incompetence of his superiors who remain adamant about making the necessary replacements. He echoes complaints for replacements of machines all to no avail albeit doing his best to maintain functional order. Our character Mofe has dreams brewing inside of him, dreams of a promised land at the end of the Atlantic ocean that caress the scalps of Lagos

Exploring Independent Journeys

Mofe

Everyone dreams of distant terrains far beyond our periphery. Mofe has Spain on his warring and strained mind. Through incessant toiling he has been able to accrue funds for a passport with ambiguous origins. He keeps toiling in the bid to raise the wherewithal to spurious letters of employment from foreign companies to guarantee his safe passage at the embassy.

Independent of that, he’s the archetypal Nigerian fraught with interior turmoil and external burdens. He resides with his sister, Precious (Uzamere Omoye) in an impoverished part of town, sequestered from all the beauty and splendour of Lagos. Not dissimilar to suffering of Job, God and the devil or fate conniving to test Mofe — Mofe faces great challenges, losing family and property while trying to achieve his dreams. He deals with family drama and legal issues, with his unsympathetic father and a cousin who complicates things further. Throughout, Mofe continues to work, untangling cables in the factory.

Rosa & Grace

We then meet Rosa (Temiloluwa Ami-Williams) and her pregnant teenage sister, Grace (Cynthia Ebijie). — Rosa is in her twenties while Cynthia is a teenager. Rosa works multiple jobs because Italy is her dream country. She strolls indignantly albeit stealthily through the world of lecherous men like her landlord who demands sex for rent and a questionable immigration broker willing to practically smuggle them into Italy if they were willing to part with Grace’s unborn infant. Upon their introduction one thing is made clear about the film ; the true antagonist is the system.

Capturing Lagos: The Cinematic Lens

Our characters do not intertwine beyond the austerity of circumstances. The Esiri brothers perhaps aren’t concerned with meddling of fates or the coherence of individual dramas. Cinematically, Eyimofe emphases the realities of the unnamed majority, thanks to the cinematography of Arseni Khachaturan —a majority that exists past the vacuous parts of Lagos far into the edge of the country, across stratas, class, ethnicities and religion.

The film clinically details the journey the search of greener pastures entails, the mountains and ravines one has to scale and cross just to find an iota of respite. And it does so with freakish accuracy. There are moments in the film where some shot choices teeter towards being waterboarded or submerged in murky waters. You are forced to grapple with the story as it happens. Eyimofe serves reminders that its story isn’t happening in retrospect; there exist men and women subverting various means just to get out of this country. They lead us to the eye of the storm, ceremoniously telling us that the golden fleece is in high demand and it’s in the cities of Spain or the steps of Italy for some Nigerians.

Eyimofe immerses you in the characters’ struggles, reminding us that these challenges are ongoing for many. It moves beyond statistics to show personal stories of desperation and the strong desire to leave the country. Khachaturan captures Lagos as a vibrant yet disjointed open-air prison, with each frame filled with internal conflict.

A Society in Desperation

Despair and desperation are central themes of Eyimofe (This Is My Desire), highlighting the precariousness of the characters’ lives. We as an audience (or for the sake of broadening the scope; a society) often find the stories of desperation negligible because excess attention is placed on the grass-to-grace rhetoric and because we adore a happy ending that rejuvenates our waning hope in humanity.

Conversely, we each know characters of this nature; some old friend with foregone plans to emigrate to England but has now resigned to fate or another friend who made there via nefarious means only to be deported. Many such cases loom around the news or anecdotes told in parties and bars. But perhaps the Esiri brothers are also concerned with the true, unbridled pessimism that permeates through this nation, a kind of pessimism that aptly says that the only method to success is beyond the shores of the home country.

You see it in immigration offices; legions of fathers and sons, garrisons of mothers and daughters, most of them indigents there, at the periodic mercy of bureaucrats, to pay for passports in the hopes that day escape the harrowing machine of the nation.

All like Mofe, Rosa and Grace, chained to their desires — anchored to the impenetrable tanglings of cords and this nightmarish part of the Atlantic.