by Remi Jordan

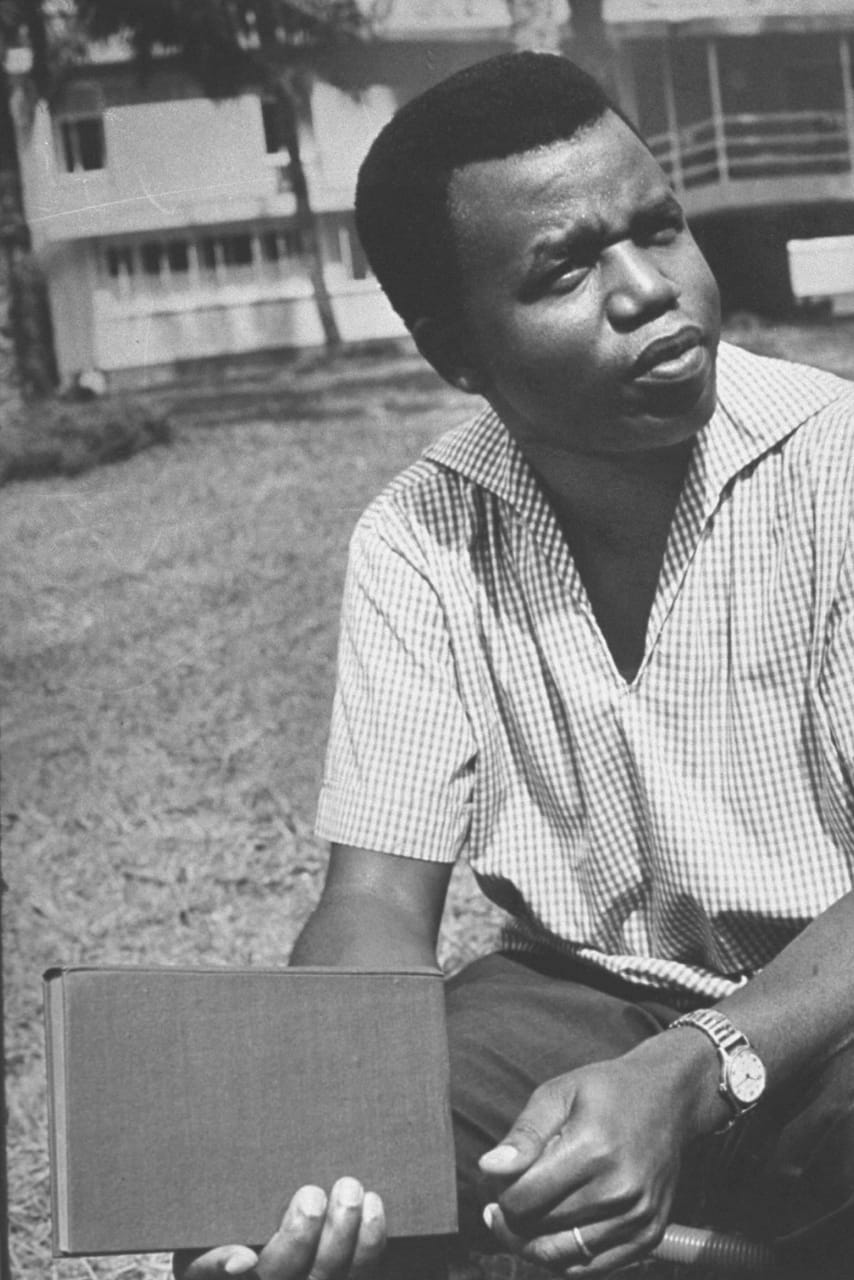

“If you don’t like someone’s story, write your own”- these are the words of Chinua Achebe to The Paris Review in 1994. Not to take away from the imperative ethos of Nigeria’s greatest writer, but that has failed to resonate with the majority of our filmmakers who are pursuing novelty in the immortal craft of storytelling. Perhaps it is time to leave the chase of an original screenplay and look to the written language that precedes the language of cinema. Perhaps it’s time for our filmmakers to consider the potential of novels and short stories.

The novel, to the filmmaker, can be a complex bible with a beginning, middle and end, but not necessarily in that order, and that description resonates with the structure of film. Although we might embellish it andwe serve it up as a way to ignite the creation of good films; it is not a shortcut or a simple page-to-screen to process. It is not an opportunity for a verbatim narrative. The adaptation of a novel is a craft. One does not plunge into a piece of written fiction on a whim.

There’s a need for a deep understanding of the story and the writer’s motives. Nigerian filmmakers lack a certain… attentiveness to stories that stem from the over-commercialisation of the arts and the dominance of mindless entertainment. The novelist, specifically the African one, for the most part, does not have the liberty of cheap entertainment. The novelist has to say something because the voice is a delicate object and there’s no room for waste. That is the beauty of the adaptation of a piece – you do not waste the voice of a story, especially a story that is not yours.

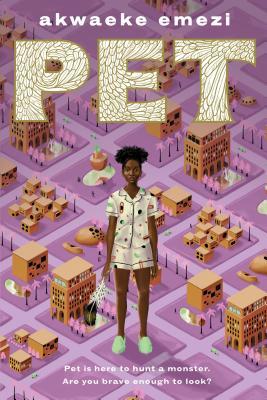

We are not in short supply of beautifully written novels (and no, I’m not talking about Chimmanda Adichie). Novels that predate Nollywood itself. Amos Tutuola’s ‘The palm wine drinkard’ and My life in the Bush of ghosts’ are seminal works of art that transcend the rules of storytelling and language. Achebe’s pre-colonial novel; Things fall apart – is widely read, considered a classic beyond our borders and has something cinematic if handled by a filmmaker who has respect for the craft of writing a novel. On the contemporary side of things, we have Leslie Arimah Nneka, Ben Okri, Helen Oyeyemi, Akwaeke Emezi, Eloghasa Osunde, and Teju Cole, all with works that are highly revered and worthy of adaptation.

These adaptations will, by extension, tell the world that our work is beyond faux morality and parodies of Hollywood pictures, and there’s something qualitative to offer the arts. In a world where content is “king” and mediocrity garners applause, it’s a disservice to our attention spans and comprehensive abilities if we don’t continue to clamour for good stories that not only entertain us but also grinds our consciousness. We need more pretension. We need the pretension of a novelist to make our best picture contender.

All of the above are not absolutes and there’s the awareness of rights and permissions when it comes to adapting a piece of fiction for screen. No one can say for sure that this is the panacea to the disease that is bad films. Original stories can still be told, are being told especially in the soon-to-be thriving independent film sub-sector of Nollywood. Still, the mainstream sector is bleeding, churning out the emptiness and asking us to make ours if we are dissatisfied with what is being given, asking us to tell our own stories if we have the resources to, telling us to forgive the cinematic sins of an industry that thrives on marketable faces and shock value. Perhaps the answer to all of that lies in the brown pages of a book read by the right filmmaker who wants to tell the story of someone else.