A tale of two paradigms.

When we tell the tales of the birth of Nollywood, we must do well to invoke the opening lines of Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities: it was the best of times… It was the worst of times. It was the age of colonial politicking, alienation, blood, revolutions and the spectacle of heroes. A century defined by the polarity of ideologies and secessionist aspirations — a country defined by oil and coups and an alias deeming the fine republic as giants.

The inexhaustible corpus of filmmaking stalwarts like Orisabunmi Oje, Andy Amadi and Tunde Kelani do not dance unechoed in the enormity of our contemporary culture. The highly-alluded home video era still lives on in the sartorial splinters of fashion (the alte counterculture) and directorial homages (filmmakers like CJ Obasi and Kunle Afolayan). But before the sobriquet Hollywood planted itself into mass consciousness, an inflexion point was needed — a defining film, a movement not unlike the new Hollywood-defining Bonnie and Clyde (1967) or the German expressionist movement in Pre-World War II Europe. Living in Bondage served as that historic inflexion point.

The best of times

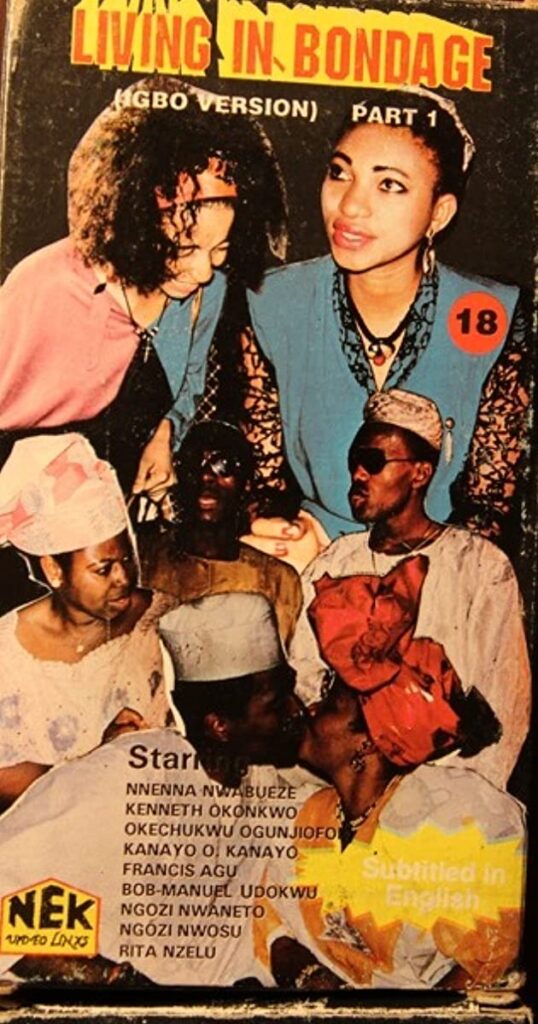

Though repeatedly hailed by many a film historian and a fraction of the masses to be the film out of the many that spawned the behemoth industry we now know as Nollywood by virtue of its popularity, Living in Bondage gestated in the ferocious albeit modest minds of Okechukwu Okey Ogunjiofor (also known for Nneka the pretty serpent) and Kenneth Nnebue, a businessman and producer reputed for pioneering the usage of VHS tapes for film production.

With one Chris Obi Rapu in the director’s chair, the two-part drama thriller morphed onto the scene as a diamond in the rough — at the time, television and VCRs, CDs were machines and peripherals of a great replacement that had befallen Nigerian cinema culture.

Tradition was dying and the vieux maitres no longer guarded the Eden of Nigerian with a flaming sword. Filmmakers abandoned the old ways for the newfangled methods — straight to video, scrappy, greenhorn, low-level productions brimming with ideas and themes that were radically reflective of the perils of the age.

The Silk Road of trade was the Alaba electronics market in the insomniac city of Lagos, where the intentional purity of art meets the engines of commerce. Films like Soso Meji (Ade Ajiboye), widely regarded as the first film produced on video in the late 1980s, blazed a trail in the nascent industry. If content is king, distribution is god — and the video film market thrived at an unprecedented rate, planting its seeds in the unformed lands of the future.

…the worst of times.

With a coup d’etat in the nation’s rearview and the continuance of the military machine of the Babangida regime at the helm of affairs, the art reflected the stringent spirit of the times. The masses flocked towards new sanctuaries like the advent of Pentecostal churches and mysticism. Living in Bondage owns a wry reputation of thespian provenance —most notably the actors it brought into the limelight: Kanayo O Kanayo, Kenneth Okonkwo, Bob-Manuel Udokwu, Francis Agu, Ngozi Nwosu, Zack Orji, Nkem Owoh etc.

The plot is that of a Faustian bargain, one we are mostly familiar with — a businessman, Andy Okeke (Kenneth Okonkwo), down on his luck, faced with a litany of obstacles, is embroiled in the classic pact with the devil and the gnawing possibilities of losing his wife to the lecherous figures that desire her. Pragmatically, it is all too easy to render the film in a post facto manner, one that dismisses the plot as belaboured and hyper-didact, but that would be a hasty assessment of Rupu’s visual language and Nnebue/Ojiofor’s parsing of the times.

With an Igbo-English dialogue, Living in Bondage was an unintended masterclass in the perils of culture, value system, greed and the neo-colonial rise of Pentecostalism. The get-rich-quick theme that would subsequently become a staple in Nollywood emerged from national dysphoria and a philosophical disquisition into socio-economic alienation. Upon a darkened canvas was the painting of a nation entangled in strife they could only have mitigated with sacrificial magic and deference to the occult. Every facet of the two-part film was poised to become the aesthetics of evil and a cautionary tale embedded in a domestic melodrama.

Where we are now.

Related: Highest-Grossing Nollywood Movies in 2024

Though Living in Bondage errs on the side of preachiness, historical significance and an unsavoury portrayal of women that suggests they are lands to be conquered by the highest bidder, it was —and still is, the film of the everyday man grappling with the appalling magnitude of the unknown and forces beyond his human control — not far removed from the allegorical status depicting the average Nigerian against systemic forces that present themselves as almost resolutely demonic.

We may amongst ourselves argue about what film merits the status of being the canonical Nigerian film and how the use of language elevates or blights the system of meritocracy. We may argue about its depiction of traditional African values and whether or not valorises a demonization of them due to a new form of Judeo-Christian crusade.

But amid the mephistophelian deals, ghosts, cabalistic wealth and forces of primordial darkness, there’s a finger on the pulse of the Nigerian audience in a cross-cultural milieu, a mass fraction of people who had their hopes and dreams decamped by a slew of coups and a civil war-induced regional ism. The commercial impact often obfuscates its thematic intelligence but when critically compared with present-day Nigerian cinema, it becomes more glaring that, though we have astronomically improved in the backend affairs of filmmaking, our mainstream output is lacking in intellectual ambition.

Safe for a few directors, our artistic metamorphosis is in a state of arrested development because commercial appeal supersedes the cinematic statement. Granted the Ramsey Nouah-directed sequel seemed as though there was a return to form but the curse of a sequel long after the release of the original often creeps up, rendering its reactionary and remedial.

But for better or worse, in a period of incomprehensible decline in our faith in the system and the rule of law alongside the hastening erosion of reason and culture, Living in Bondage holds the stage of relevancy as we saunter more towards late-stage capitalism, a materialist culture and a workforce in the business of bloodletting. Kenneth Nnebue, Ogunjiofor and Rapu possibly never set out to create a lingua franca for now booming Nollywood, but you can see splinters in their vision in almost every production since its release, beating ceaselessly into the past.