by Remi Jordan

Painterly.

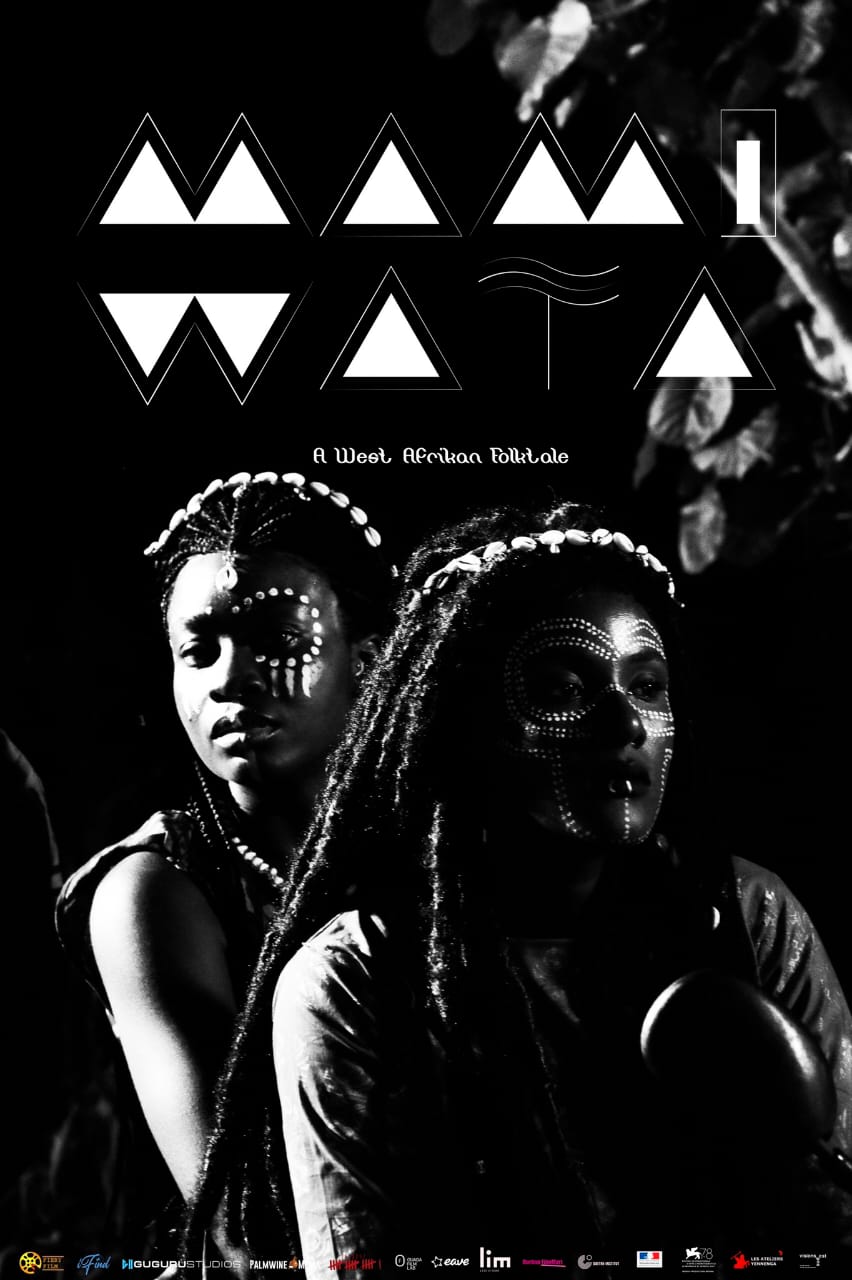

A cliché word when describing surreal directorial style or a visually effulgent film that evokes something indescribable in you. But it’s the word that best fits C.J Obasi’s third feature titled Mami Wata. A folkloric painterly tale crafted by the brush strokes of a man from a newer school of thought. The monochromatic feature does not burn bright because of the artful nature of a black-and-white film but because of its spirituality and sojourn towards the arcane.

Without giving out the substantial parts of the narrative, Mami wata is unabashedly African. Not just in the mythological dissections and the tales about spiritual realms specific to the multicultural landscape of the continent, but in the way it invites the chilling wind of modernity. It is a painterly cascade into the African complexity, the tussle between the arcane and the practical. Obasi’s worldview takes precedence here, not just in the plot but in his visual language and how he sees the medium of cinema. To him, one could suppose, the art form is the closest thing to morphing into an angel from the silence of nothing. The goal here, one could suppose again, is the lack of economy.

In the adumbral world of Obasi and Lilis Soares(cinematography) lies the village of Iyi, befallen by malady and anchored to the mercy of an old deity and the questionable position of the mendicants of this deity. We are thrown into the biblical. At the epicentre lies Mama Efe (Rita Edochie), the unwaveringly devoted one, we see through her the cost of faith and the inability to grapple with the death of belief. Through her actions surrounding the death, the event that drives the film forward. We see failings of a prophet and a healer who against all reason needs to you to believe that they are the one true voice. Her daughters Prisca (Evelyne Ily) and Zinwe (Uzoamaka Aniunoh) add to the story’s dynamism and commentary on the complexity of family. Both sisters serve at the pleasure of the deity and their mothers but with varying convictions. They both share an unbelief but it stems from duty to their mother. Prisca stands as the one who values survival over self-interest or atheistic leanings, despite her lack of faith, she serves as the driving force for her sister, the one primed to carry on her mother’s mantle yet feels disillusioned and unwilling.

The sisterly dynamic draws us in further into the conflict of faith when put against duty. There’s a scene that enunciates the tussle of modernity versus doctrine, when a medical doctor comes to town with vaccination for the children through Prisca only to be met with the reluctance of Mama Efe. She later obliges but not without attributing the success of modern medicine to her God. Here Obasi says – evidence is not enough when magic promises heaven.

On the other end of the spectrum, we have Jasper (Emeka Amakeze), a rebel with new ways who found on the shores of Iyi and Jabi (Kelechi Udegba), the revolutionary, the skeptic and figure of dissidence – militarizing his way against Mama Efe and her authoritarian leanings. They both as the coming of a new world, the detritus of colonisation. The pathos of the film is the wrestling of faiths, two forms of faith in a ring trying to one-up each other endlessly. Lila Soares’ cinematography is beyond black-and-white as the archetypal art house film choice – the shadowy hues and the dream-like shots are within a context – they represent a push-pull of ideologies.

In Mami Wata, some of the characters want to move forward and watch the old gods burn, some of the characters want to retain the doctrinal status quo. You get the eerie sense of a world drowning in ambivalence and a series of revolts. Every acting performance here marches towards something – an unknown. As seen in the film Jasper and Jabi lead a band of rebels against Mama Efe, an insurrection against the old ways and Mama Efe’s unwavering faith in failing gods.

Again, Mami wata is unabashedly African. How do you talk about African film? Is it the spirituality of the continent? Is it the depiction of negritude? Is it a hyper-politicised film about coups and dictators? – you really can’t write one that exemplifies THE African film but you can write one that exemplifies the multiplicity of the African experience within a context. Obasi has made a film about a specific topic here, the old against the new, and the viciousness of the faith. This isn’t experimental or avant-garde, it’s simple. Mami wata is a simple film about a world where there are no answers. Just water. The oceanic motif is representative of the arrival of old and the new and the tides that bring them.

Like the goddess, Mami wata, we are tethered to the ocean as we watch the plots unfold.

A sundance favourite with no commercial appeal in its hometown. Revered abroad, even winning the special jury prize for cinematography and deservingly so. As elegant and brimming with substance as the film is, it doesn’t appeal to the majority of the audience in Nigeria. We can’t attribute that to the intellectual capacity of the audience totally. People want to see beautiful things. We can only hold the film houses accountable who see profit as precedent over art and care only for the blockbusters and comedies. Those kinds of films aren’t inherently lesser but they are ubiquitous and do not make way for the quiet ones with even the straightest narratives, how much more the experimental ones that dabble in the abstract. We need to make way for films like this because it’s the cinema of now.

Mami wata isn’t without its faults, one can say it leaves things unfinished if you are a sucker for tight-ended stories but it’s a miracle of a film. A stunning feature rich in visual language and performance. Not just an indie darling, it feels reductive to regard it as that. We should refer to it as a triumph, a step in the direction, a great beauty from the wata.