by Remilekun Jordan

The divine nature of art, by ineffable design, blooms through an evolutionary process, cascading through time and leaving a mark in the record for reference, for study, for admiration — for renaissance. With drama, the Greeks had the classical period, the hellenistic period and the age of new comedy. Paintings have morphed from the ancient art in cave walls painted by the first men to Byzantine art, the Renaissance period, baroque art, impressionism, modern art, contemporary art.

Every epoch with its technique, approach and reflection of the world state ; the conferred value of kings and Lords, the ambitions of peasants and vassals. Here we set our quizzical eyes upon Nigerian 70s cinema, not necessarily from its accurate inception, but from the age of disco and coup d’etats, progress and oil. Barely remembered for what it was, only told through gold-tinted glasses— the 70s, the decade of numerous booms.

Ample politicking and significant developments had occurred to promulgate the progress of cinema prior to the wake of the Nigerian 70s cinema era —the allure of our independence in 1960 had placed Nigeria on a path of industry. However, we consider the Nigerian 70s cinema as the peak of our cinematic golden age by virtue of the industrialization of the nation itself in tandem with the economic prosperity that followed the oil boom.

This was a decade of nascence; our foray into ethos of the ever-dynamic Nigerian spirit, we were telling our narratives with familiar voices aching to shed its British engraved chains. This portion of a post-colonial Nigeria was akin to a quasi-renaissance ; the rejuvenation of the Nigerian spirit, though battered and subjugated, prevails hand in hand in the teething stage of a nation. Nigerians found solace and tranquillity at the cinema before they found it in the churches, for what was holier than dreams told by countrymen superimposed by the projectionist on the dimensions of screens existing in the cross-country multiplexes from Lagos to Enugu.

The Gowon administration accelerated the growth of cinema with the Indigenization Decree of 1972, this served as a legitimization of the art form and its distribution. Though its lasting impact remains a topical issue amongst historians, politicos and scholars, the Decree aimed at propagating economic independence whilst abating foreign dominance in key sectors in the blooming Nigerian economy. Consequently, foreign-established cinema houses were turned over to indigenes therefore facilitating the rise of Nigerian as a powerhouse. Another independence had occurred there constitutionally, a true foray into the Nigerian spirit displayed upon the imported screens about stories told by our own countrymen.

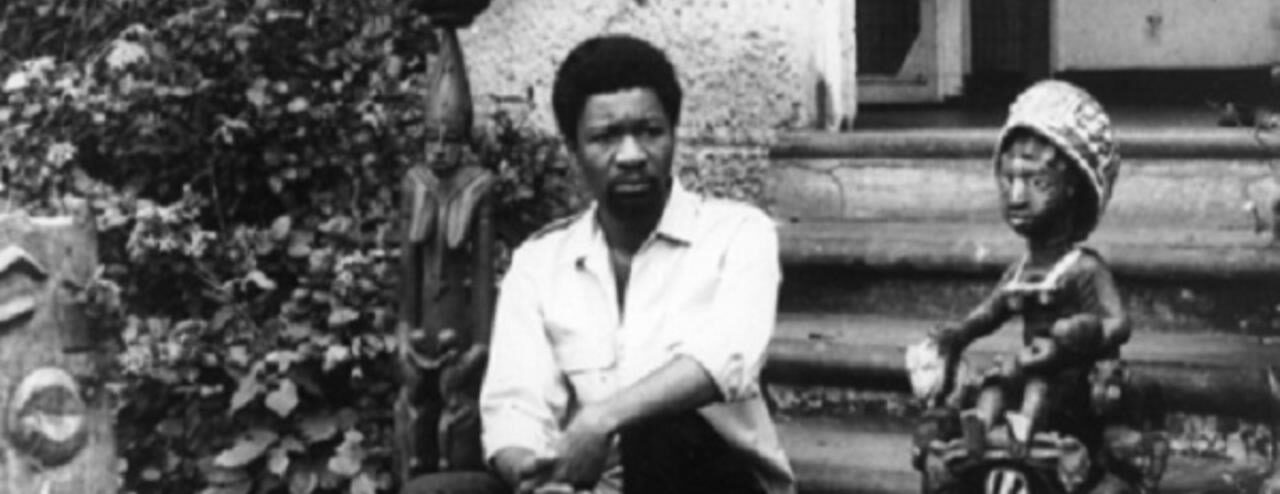

Uncoupled from the policies and precedence, the minutiae of Nigerian 70s cinema bloomed in the art itself. Theatre practitioners morphed into filmmakers, taking the gifts of the stage to the presence of the camera — our classics were born. Films such as:

– “Kongi’s Harvest” (1970) – based on a 1965 play by Wole Soyinka

– “Dinner with the Devil” (1975) – by Wole Amele

– “Countdown at Kusini” (1976) – by Ossie Davis

– “Bisi, Daughter of the River” (1977) – by Jab Adu

– “The Rise and Fall of Dr. Oyenuzi” (1977) – by Eddie Ugbomah

– “Musik-Man” (1978) – by Ola Balogun

– “Black Goddess” (1979) – by Ola Balogun.

Not limited to the aforementioned films, the cinema of the seventies built the foundation of what we shall come to know as Nollywood amidst the Fela crooning and the politico-moral ambiguity. Eddie Ugbomah’s The Rise and Fall of Dr Oyenuzi (1977) has been regarded by the cohorts of that era as an indubitable classic. A crime drama recounting the daunting criminal exploits of a real life armed robber by the name of Dr. Ishola Oyenusi who ravaged the once serene streets of Lagos in the early 1970s. A certain post-civil war disillusionment pervaded the nation that further entrenched the popularity of the film and the figure it examined; Oyenusi through cinema and crime became a folk hero and a force of evil, a true Shakespearean player who met his Waterloo through treachery and recklessness. This was many of the numerous forays into the malleable complexity of the fairly new nation of Nigeria.

Ola Balogun’s Nigerian-Brazilian film Black Goddess(1979) explored the spirituality replete in Yoruba and Brazilian culture. Through the use of magical realism and traditional music, Ola Balogun mounts us on a transatlantic journey through culture and identity of the diasporan strain. We are sauntered towards the harshness of colonialism and the slave trade as we, the urban dwellers, wrestle with a struggle germane to the contemporary. Many such films of this nature defined the vivacity of the age; identity conferred, identity conjured, post- civil war disillusionment, the eeriness of progress after national tragedy and divide, the eeriness of progress amid ethnic tensions, the search for dimensionless spirituality.

The readers of this article, one might mathematically assume, are in the younger demographic — unbothered by the provenance of homegrown cinema, the so-called classics or the policies that begat the vibrancy of the decade. That laissez-faire attitude can be partly attributed to the dislocation from the past and the improper documentation and teaching of the arts from a formative level. The works of Hubert Ogunde, Wole Amele, Eddie Ugbomah et al are essential not solely to the cinematic form but to the holistic history of the nation — to the complexity of contemporary Nigeria.

To paraphrase Jean Cocteau “A film is a petrified fountain of thought” ; here our films are a fountainlike compendium of anxieties embalmed by war and transitory progress, a fountain at the risk of being forgotten, misapplied and inadequately written about. The scythe comes from all decades, leaving in its wake the remains of its aughts. Coups ravaged the rest of the decade, if you listen closely you can hear the tedious breaths of the golden age under the rubble of FESTAC 77. The undeterred influx of television flooded the homes of Nigerians who were ready to go forgo the joy of the outdoors for the comfort of their abodes as the military boots paraded the streets. Everything was lost to the economy and the devaluation of local currency. Films were no longer for the big screens but for the home-video format. The art form suffered a severance by a thousand cuts by way of free market evolution, ushering in a new age as the oil barrels became our grandest exports. Thus the screen of the Nigerian 70s cinema faded to black.