By Johnson Opeisa

More often than not, when an athlete decides against representing Nigeria in favour of foreign options, irrespective of the many caveats, it’s the best decision. Favour Ofili’s case was no different.

The more you think about Favour’s decamp to Turkey, the more you see it for what it quite literally is: a long-overdue move by an athlete whose career has been repeatedly hampered by the Athletics Federation of Nigeria’s (AFN) chronic dysfunction.

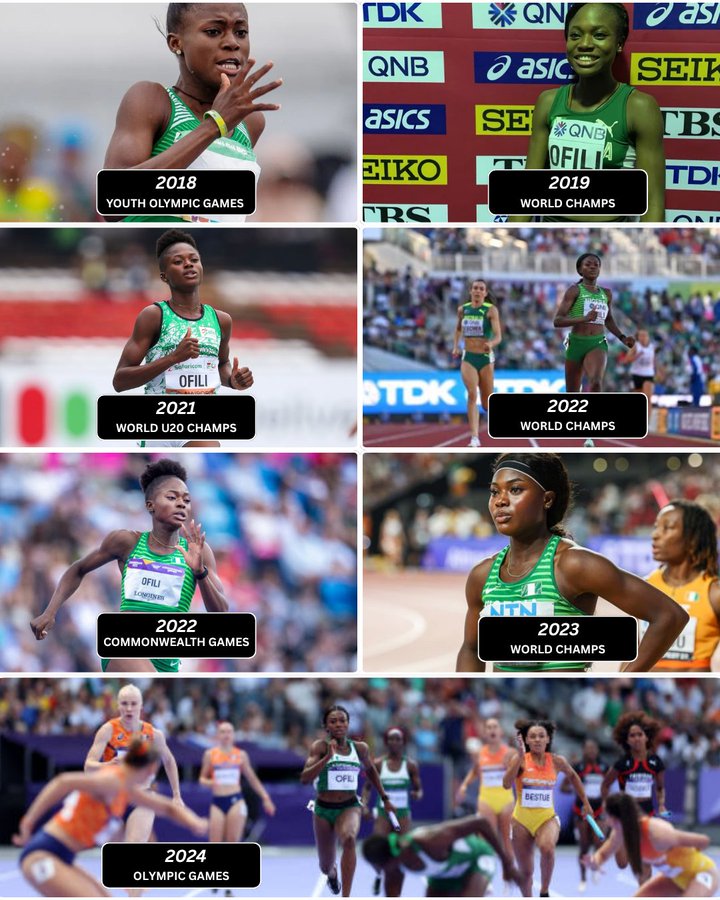

A Nigerian-born and slightly bred track and field star, Ofili, 22, after about a decade sprinting in Nigerian colours, will now compete for Turkey. The news has been circulating since Sunday, June 22, and while there hasn’t been an official statement from her camp, no one needs to be told the final straw was the Paris 2024 Olympics, where the AFN’s blunder led to her missing the 100m event despite qualifying.

It mirrored the disaster at the Tokyo Games four years earlier, where she and nine other Nigerian athletes couldn’t compete because the AFN, again, failed to pay for the out-of-competition test (OCT) for the athletes to ensure their minimum drug-testing requirements were met.

Favour had cried out then. She warned, though she competed in the 200m — reaching the final and finishing sixth — the AFN’s blunder in not registering her, and altogether denying Nigeria a representation in this event and Ofili a medal shot (having qualified with 11.06 seconds which surpassed the Olympic qualifying standard of 11.10 seconds), had marked a rupture that the inept federation couldn’t possibly remedy.

“This is not the first time you guys are doing this, so don’t think this is over, because it’s not,” part of her outburst on Twitter back in August 2024 read.

“If those responsible are NOT held accountable for taking this opportunity from me, neither organisation [AFN and National Olympic Committee (NOC)] can EVER be trusted in the future!”

In hindsight, those phrases bore it all, with her intentions all but declared in the capitalised words. The future the Port Harcourt-born athlete spoke of is here, and part of its early reality is the severing of professional ties with her birth country, which she had represented for about eight years. Since she broke onto the scene properly at age 16 at the 2018 Youth Olympic Games, Favour has gone on to represent Nigeria across multiple international competitions: four World Championships, plus stints at both the Commonwealth Games and the Olympics.

Still only 22, the remainder of Ofili’s international career will be in Turkish colours, thanks to the AFN.

The Federation, now only a few weeks into yet another Tonobok Okowa-led administration — the same man under whose watch the chaos of both Tokyo and Paris unfolded — has responded to Ofili’s exit in predictably familiar and deflective fashion.

“She is a promising athlete with huge potential,” Okowa said. “She has prevented the Federation from reaching her, and all efforts to heal the wounds caused by the 100m Paris Olympic Games omission have proved abortive.”

Interestingly, just days before Ofili’s switch to Turkey surfaced online, relay athlete Olayinka Olajide, popularly known as AJ Gold, had cheekily predicted that Okowa’s re-election would trigger an exodus of Nigerian athletes to the US, one of the preferred destinations for embittered athletes. “Another tenure for President Okowa. More athletes to the USA,” AJ Gold tweeted.

With more exits potentially on the horizon, revisiting the cases that predate Ofili’s helps unpack why future walkaways may be no less warranted, given the AFN’s refusal to change its spot.

Before Favour Ofili: The AFN’s Trail of Talent Drain

Before Favour, trust the AFN’s chronic mismanagement to have already left a trail of Nigerian athletes in its wake. As much as it’s important to go into some of these instances, it also goes without saying that athletes switching nationalities isn’t peculiar to Nigeria alone. It’s quite common globally. Though nationality switches are tightly regulated in international football, World Athletics operates with far more leeway. This has encouraged a steady stream of athletes, mostly Africans, to constantly explore available options over the years.

The phenomenon is as old as it gets, but there was a particularly striking moment ahead of the 2004 Olympics where Qatar and Bahrain poached no fewer than seven top Kenyan athletes to join them for the Games. Some of the athletes cited the intense internal competition within Kenya’s ranks as the reason for the switch, but the towering financial capabilities of the Gulf nations cast doubt on the veracity of the claims.

In Nigeria’s case, the athlete’s quid pro quo has mostly revolved around a combination of better facilities and personnel, structured development pipelines, and a generally competent administrative system, all of which the AFN has historically been bereft of.

Take Florence Ekpo-Umoh, for instance. In 1995, the quarter-miler took advantage of a Nigerian training camp in Germany to defect. Justifying what was seen by some as insubordination, she said, “I switched allegiance to Germany because I had this feeling that if I stayed one more year in Nigeria, my career would end. Germany is far better in terms of taking care of athletes, and they are well-organised. Their athletes come first before anything.”

Perhaps more famous is the case of the legendary Francis Obikwelu. One of Nigeria’s most gifted athletes, Francis won a World Championship bronze medal in the 200m in Seville in 1999, where he also set a standing Nigerian 200m record of 19.84s. His commitment to the country, however, ended in 2001 after the AFN abandoned him during a career-threatening injury. In a recently circulated clip, Obiekwu recalled how the federation went as far as telling him, “We can produce another Obiekwu.”

Francis Obikwelu was injured and needed $15k for treatment. The money was approved but disappeared. He switched to Portugal and helped Portugal win it's first ever Gold medal at the Olympics. pic.twitter.com/mCvH8tztqa

— Aji Bussu Onye Mpiawa azụ 🇨🇮 (@AfamDeluxo) July 2, 2021

Competing for Portugal, he went on to win Olympic silver in the 100m at the 2004 Athens Games, where he set a then-European record of 9.86 seconds. He became the first male athlete to win both the 100m and 200m at the European Championships and was subsequently voted European Male Athlete of the Year in 2006.

Similarly, Femi Ogunode’s story also feeds into the failures of both past and present AFN administrations. After qualifying for the 2007 All-Africa Games and the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the federation, somehow, failed to include Ogunode in Nigeria’s final rosters.

Around 17 at the time, Ogunode who had risen to the limelight from running for the University of Ibadan accepted an offer from Qatar following the AFN’s blunder and has since gone on to win multiple titles for the country, notably setting an Asian 100m record of 9.91 at the Asian Athletics Championship (later surpassed). The former fastest Asian man would reflect later on how the move to Qatar was a timely and calculated risk to escape the throes of nepotism in Nigerian athletics.

The AFN’s Unending Cycle of Chaos

Even the longest night is said to end with dawn. But in the case of the AFN, the chaos of the past has only become the template for its present, after transient changes in administrative leadership over the years.

The consequences of this recycled incompetence were evident in the case of Annette Echikunwoke. Born in Ohio, USA, Echikunwoke’s athletic abilities were developed in the country, but for some reason — possibly in hopes of a faster route to Olympic debut — she decided to represent Nigeria at the Tokyo Games. She went through the Nigerian Olympic Trials, where she set national and African records in the Hammer Throw with a mark of 75.49m. With such potential, expectations were high for the American-born thrower to make a mark at Tokyo, but what stood in the way was the AFN’s refusal to pay the OCT, which disqualified her.

Four years later in Paris, the 28-year-old would go on to showcase her potential, throwing 75.48m to win silver at the women’s hammer throw event. All it took was representing the USA, which couldn’t have been a better outcome for both parties, as it was also the first medal the country would ever win in the category.

Reacting to the fallout, President Okowa, who was in the early days of his first tenure, classically shifted the blame to his predecessor, Shehu Ibrahim Gusau, who was all but forced out of power after being charged in court for alleged criminal breach of trust and cheating.

Having also defiantly led a factional AFN administration for a while, Gusau left behind a legacy of dysfunction that still defines the AFN today. But it doesn’t absolve Okowa from the disaster of the Tokyo Games, and certainly not the Paris edition, which happened entirely under his leadership.

To date, no one has been held accountable for the Paris debacle. The two key figures publicly identified as the central figures in the embarrassing episode, Rita Mosindi (then Secretary General) and Samuel Onikeku (Technical Director), are still very much in the ecosystem. It took another audit committee, which found Mosindi guilty of misappropriation and misapplication of funds, to sideline her earlier this year, while Onikeku carried on as Technical Director until recently and has now been sworn in as part of the new administration following the June election that ushered Okowa back into power unopposed.

This poses the question: as an athlete with options, what’s the incentive to continue with a system that has consistently rewarded those who’ve sabotaged careers with even more time to keep doing so?

This is a federation that can hardly boast of a significant contribution to the development of its athletes. A considerable number of Nigeria’s current top athletes owe their success on the global stage to their own resolve, backed largely by foreign institutions that supported them with athletic scholarships.

The newly decamped Ofili, for instance, received a major boost from her scholarship with Louisiana State University, where renowned coach Dennis Shaver has so far been her personal coach since 2021. In the same vein, the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) played a major role in the development of world record holder Tobi Amusan, who joined the college in 2016. Divine Oduduru also benefited from his time with the Texas Tech Red Raiders.

Such instances only deepen the sense of the AFN’s irrelevance in the careers of most athletes and make their (discretionary) decision to eventually break off even more understandable.

But beyond the threat of a mass exodus is a deeper problem: the evident gap in the country’s talent pipeline. Nigeria, by virtue of being a youth-populated nation, like much of Africa, should never be short of talent. The problem lies in identifying this talent and subsequently developing it into world-class potential, a process and responsibility the AFN has consistently failed to stay committed to.

The entire situation is a ticking time bomb. The AFN has long shown itself to be more reactive than proactive when it comes to matters concerning the welfare and progress of athletes. It does little to build or sustain talent pipelines. It offers no clear developmental structure for young prospects. It hardly provides consistent welfare and operational support for its athletes at critical moments. Its leadership displays zero accountability, an aversion to excellence, and a blithe disregard for the ethos of administrative duty. It has, in many ways, come to stand for everything but the very core of its existence: the athletes.

This kind of federation is a burning building. It has always been. The red button only gets triggered ahead of major international competitions, and for far too long, that has been the pattern.

But when does someone finally put out the fire?