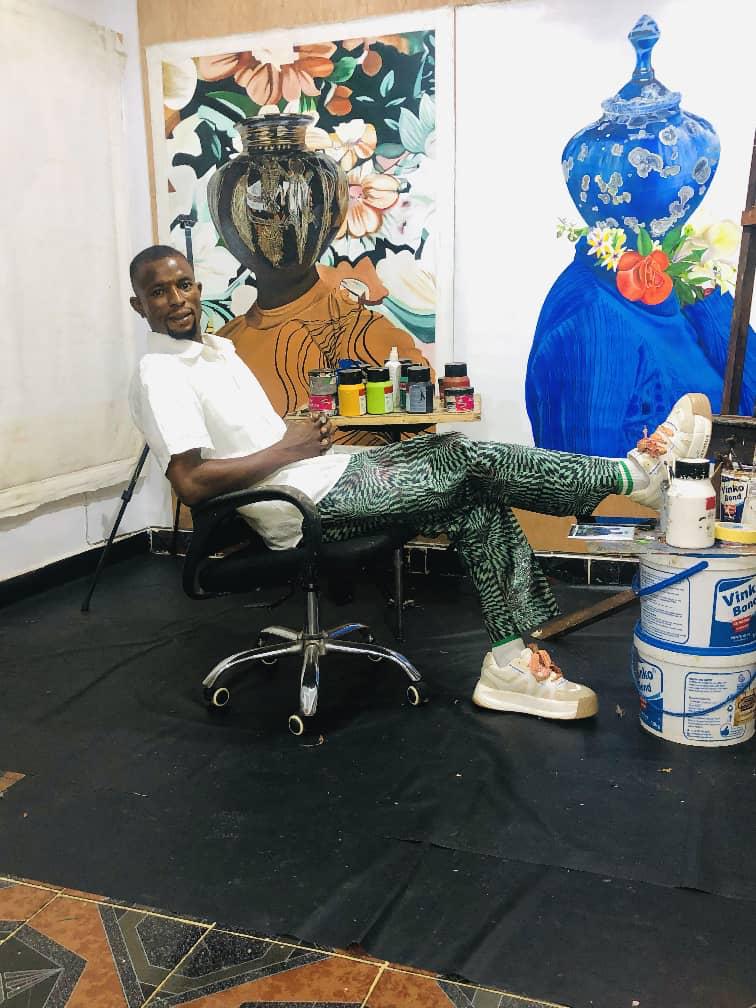

by Frances Akinkuoye

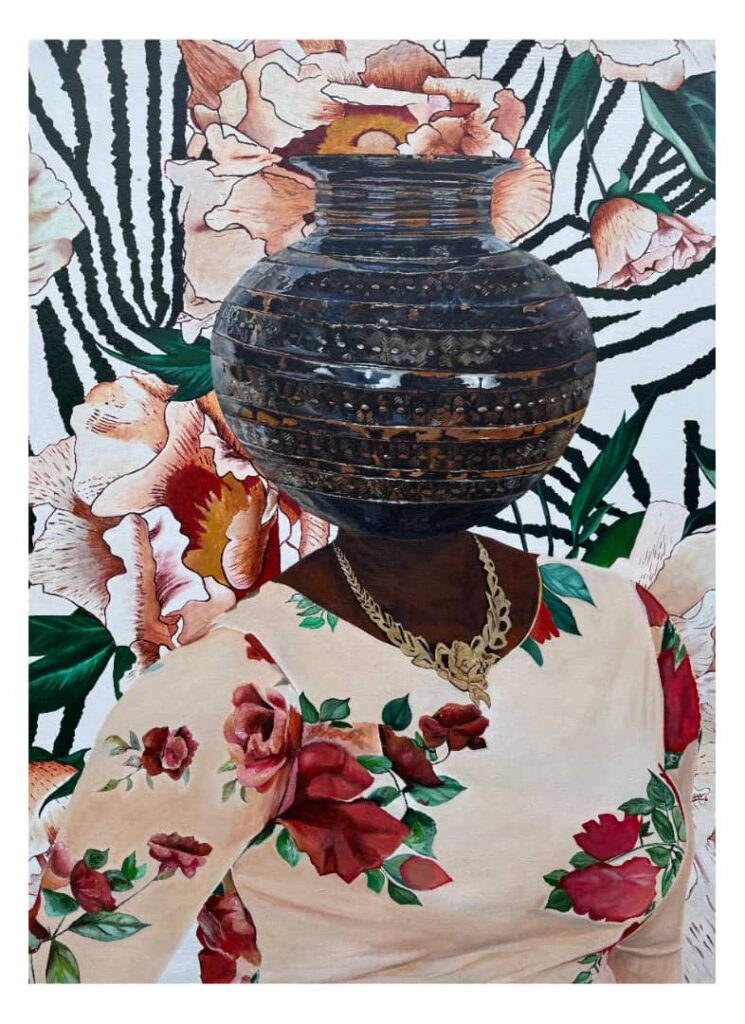

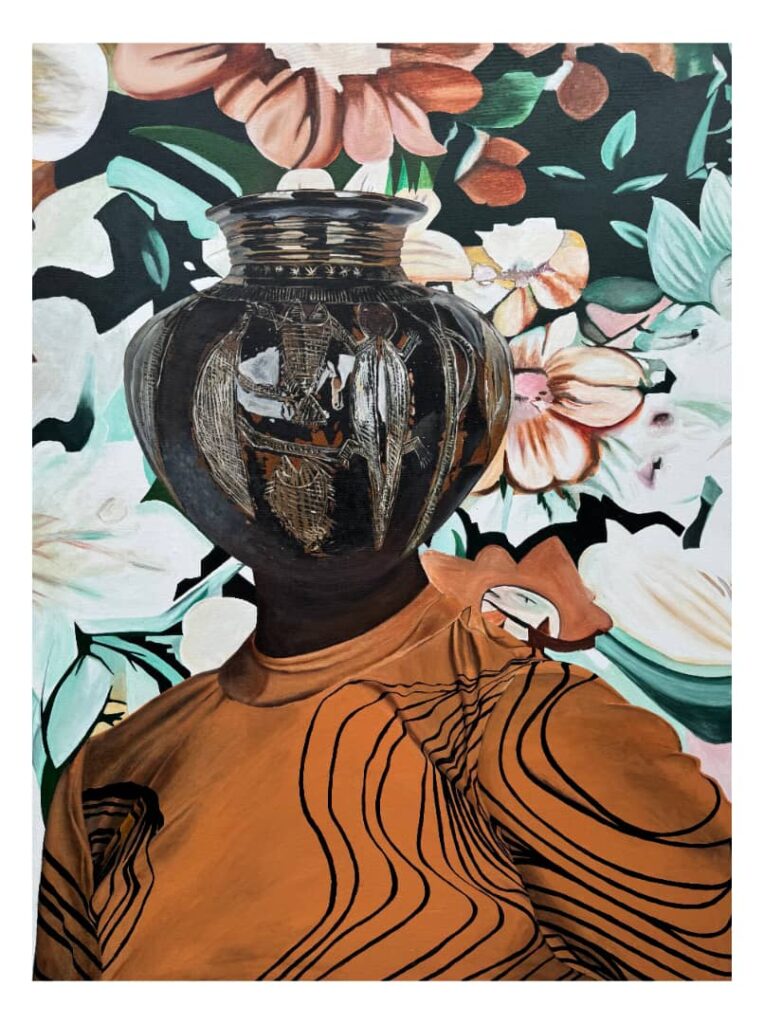

Growing up in Ipetu Modu, a town in Osun State that is embedded in Yoruba mythology, artist Hezekiah Obidare has always been surrounded by clay, the same material Obatala, the deity of creation, is said to have used to mould human heads and destinies. Today, clay and its symbolism are central to Obidare Hezekiah’s practice, most recognisable in his striking portraits where his subjects bear earthen pots as their heads. These works, at once surreal and symbolic, have become the defining motif through which he interrogates identity, spirituality, and the unseen weight of cultural heritage.

His work explores identity, spirituality, and the tension between tradition and modern existence. For Obidare, the pot is more than a vessel; it is a metaphor for destiny and the unseen weight of cultural heritage. Through painting and a deepening interest in sculpture, he covers the gap between ancestral memory and contemporary realities.

In this conversation, Obidare reflects on the turning points in his artistic journey, the mythologies that shape his practice, and the role of art in rediscovering identity and community.

Frances Okuwakorede: It is believed in Yoruba culture that the head is the prominent part of the body. As a Yoruba person, why then did you put pots on the heads of your subjects?

Obidare Hezekiah: I came from Ipetu Modu in Osun state, Nigeria, where there is a massive deposit of natural clay. Because of this, it is believed with the Yorubas, that Obatala, Oba Mori Mori ( the one who moulds heads) as instructed by God, took on a task at Ipetu Modu to shape not only the physical heads of humans but also their destinies and identities.

FO: This means that the pots that represent the heads of your subjects are not just pots, but they represent a person’s identity?

Obidare Hezekiah: The head, or ori, is sacred with regards to it’s making; it is our eleda (destiny), the part of us that defines who we are and who we will become.

For me, the pot becomes the perfect metaphor to tell this story. A pot, like the head, is a vessel. It carries, holds, and preserves. Just as a pot holds water or food, the head holds our thoughts, our identity, and our destiny. So when I place a pot on the head of my subjects, I am drawing from this Yoruba cosmology: the clay of Ipetu Modu, the creation story of Obatala, and the symbolic weight of the head. The pot is not decorative it is a visual language for identity, a reminder that we all carry something that shapes and defines us.

FO: A person’s head defines the person; it means you tell a story that surrounds identity?

Obidare Hezekiah: Yes, as I mentioned earlier, the story is about identity, and it is so personal to me. Where I come from, the locality has a massive deposit of the natural, earthly clay. Due to this, one major work of the people is moulding clay, a practice that is not only functional but also deeply symbolic within Yoruba cultural mythology. Clay is believed to be the very material through which Obatala shaped human heads and destinies, making pottery and clay work more than just a craft is a continuation of a sacred story of creation. Each vessel echoes this heritage, reminding us that to mould clay is to participate in the act of shaping identity and existence itself.

FO: What do you mean when you speak of the deep history of the general Yoruba cultural mythology?

Obidare Hezekiah: In Yoruba mythology, Obatala is believed to have been given authority by God to mould heads. To every human that has a head, Obatala, Oba mori mori moulded everyone’s head and not just our heads but our destinies that defines us. It is also believed that he carried out this task in Ipetu Modu because of the massive deposit of clay that is there.

FO: Wow, that is quite interesting, an enriching part of Yoruba cultural history. Why did you choose to explore this Yoruba cultural mythology?

Obidare Hezekiah: When the world deals with you and confusion sets in, it is best to find your way back home. I was a person who did not care about history, hometown, or whatsoever. All I believed in was to get up very early in the morning, bounce out to work, hustle and make money, which became a routine. I was a machine that worked 24/7, only to never rest. That made me practically lose my sense of self, and the question “who am I” kept popping up in my head; then the search began.

FO: The sense of self-questioning brought up a hunger for research into you?

Obidare Hezekiah: Yes, I needed to know who I was, I practically had to shut down my routines to a maximum level to focus solely on my identity crisis, to find my real self, and after that to be able to help others find themselves.

FO: As a young man, completely shutting down your daily routines couldn’t have been easy, especially with the responsibilities and expectations that come with your gender. How were you able to navigate that?

Obidare Hezekiah: Although a few times I still work, it was a priority; I picked knowing my identity first because it defines me. If I don’t know anything about myself, then I am nothing. A state of nothingness brings no value to the amount of work I do whatsoever, so, the search for identity for me was a do-or-die affair.

FO: How then did you come about knowing more of your history, your identity?

Obidare Hezekiah: I decided to step away from the constant rush of hustling. I returned to Ipetu Modu and started immersing myself in what had always been around me. I visited traditional clay and pot-making sites, spent time with elders and families who had preserved these practices, and listened to the oral histories of the town.

That was when Obatala’s story took on a new meaning for me. It no longer felt like a distant myth; it felt like a reflection of my own search for identity.

By slowing down, I was able to tune into the rhythms of the land and its history. That process opened my eyes to my heritage and gave me a clearer sense of who I am as both a person and an artist.

FO: That is a tough one. The journey of self-identity and your process of documenting the story, how has it been for you?

Obidare Hezekiah: When I first started, I was bewildered. I naturally have an interest in moulding with clay, which I have constantly tried out even without the foreknowledge of my historical culture. Getting to know this story has been very interesting and enlightening. I can now define why I do some things, I can explain them, get rooted in them and inspire others through them. It has really been an interesting and self-revealing journey.

I feel so alive because I am not just working; what I am doing now, the story I tell, has immense value to offer to people. The majority of us humans, Nigerians specifically, pass through this thing called an identity crisis.

We don’t know ourselves, we don’t know our cultural history, histories that are still pure and untapped, we often just do a lot of things randomly, not knowing they are really part of us, and they define us. Naturally, putting a pot on a human head is very controversial, and people would want to know why it is like that. That allows me to constantly tell my story of identity to people so that they can go back and find themselves.

When we all do find ourselves, it helps us to build a community of self aware people, people intentional about what they do because they know why they do them, not because they think it is circumstantial which helps them to be very passionate about the things they do and they will carefully with a guided tour do beautiful things and achieve a lot of things.

FO: This is a very beautiful path to walk on. I believe more people will be helped through your deep story. Currently, you paint on canvas, speaking of you having a natural interest in moulding with clay, do you hope to explore it too?

Obidare Hezekiah: Absolutely, clay is a very interesting medium to use because of its plasticity, and I will definitely explore the medium as much as I can to keep telling this same story and inspire others.

FO: Thank you so much for sharing this amazing story. I hope it inspires another person to take up the mantle and get on the road of self-research, historical/cultural information, finding themselves, start an intentional living, and inspire other people too.

Obidare Hezekiah: It is a great pleasure to share my story. Thanks.