By Akinwande Jordan

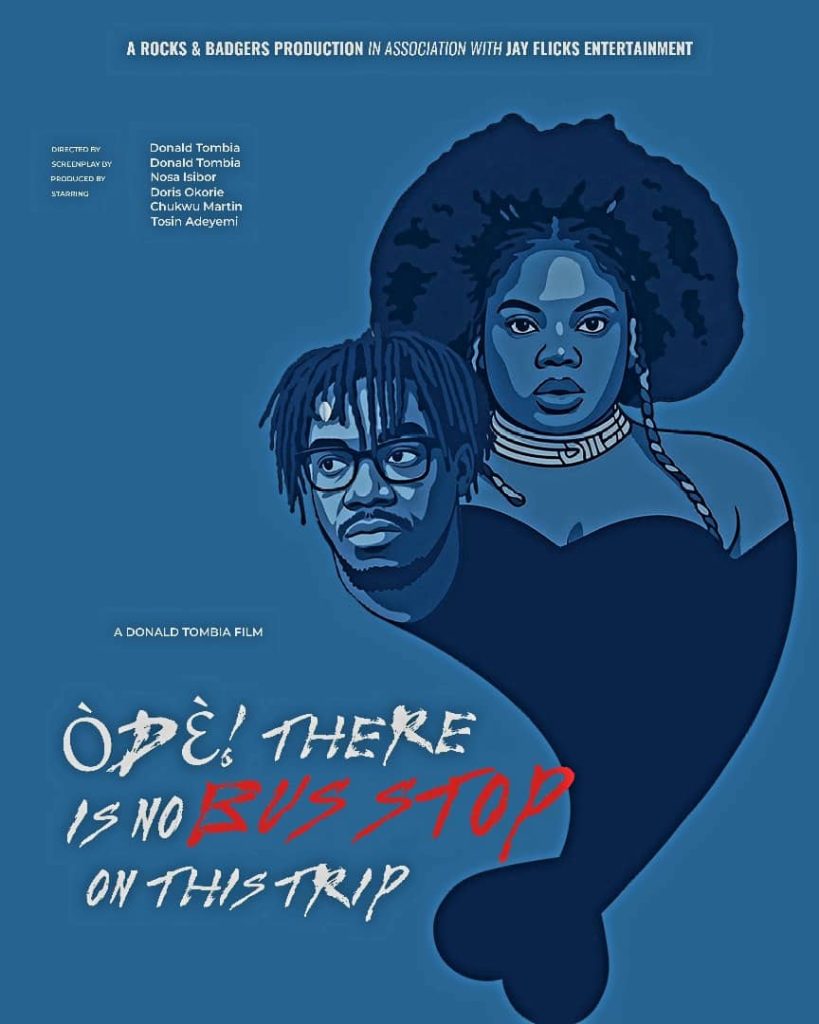

The system is quite the implacable cannibal. Nothing stops its discriminatory ferocity. We are made to witness the first-hand dissemination of capitalistic violence and structural imbalance every day, without ceasing. Donald Tombia’s Òdè! There Is No Bus Stop On This Trip unfolds for the most part in a single room, yet it contains an entire nation’s fatigue. Compressed into a microcosmic languid disaster.

Ejikeme and Akumjeli, a young couple, move through their days like tenants in someone else’s dreams, repaying debts, enduring insults, planning a birthday that feels more like an act of defiance than joy. The apartment they share is small, but the walls seem to close in with each passing scene. Tombia turns domestic space into psychological territory, a chamber where poverty becomes both the setting and the story.

The film recalls the quiet dread of Franz Kafka’s The Trial: the sense of being trapped in a system too vast and absurd to name. However, unlike Josef K., Ejikeme is accused not of a crime but of existing within a structure that refuses to make sense or offer any reprieve. His debt, his job, even his love life are all governed by forces, faceless institutions, and digital creditors that hum in the background like a low, mechanical prayer.

Tombia captures this Kafkaesque anxiety through form rather than dialogue. His camera rarely moves into the bevy. The edits are hesitant yet replete with the eye of a formalist, often cutting just a second too late or at the right cue, forcing us to stay inside the moment of discomfort.

Surrealism seeps in without fair warning. Colors shift mid-scene, sound wavers, shadows stretch unnaturally. Nothing overtly magical happens, yet reality trembles. Tombia doesn’t use these effects to stylize poverty but to show its psychic distortion—how life under unrelenting pressure bends perception itself. The result is less a story than a condition: time loops, days blur, and meaning leaks out of language.

Visually, the film belongs to a new sensibility emerging in Nigerian filmmaking—one that values atmosphere over message, texture over plot. Tombia’s palette is muted but expressive. The sound design, sparse and sometimes disorienting, builds unease without resorting to melodrama. Every technical choice seems to whisper the same truth: there is no escape.

What’s striking is the restraint. Òdè! has no grand speeches, no moral anchor. The toxic boss remains only a voice on the phone, bureaucracy incarnate. The couple’s conversations circle endlessly, echoing the film’s title—there is no bus stop, no point of rest. Even love becomes mechanical, something performed out of habit rather than hope.

In its overwhelming silence, the film achieves a rare precision of the tense undercurrent. Tombia understands that despair doesn’t always scream; sometimes it just repeats itself and beats us into submission. But in that repetition lies the truth of the film: a life caught between motion and paralysis, progress and collapse.

Òdè! is not only a film about multidimensional penury; it is a film about social entrapment. Like Kafka’s The Trial, it stares into the machinery of existence and finds no exit, only endurance.