by Remilekun Akinwande

Jean-Luc Godard once said that all that you ever need to make a film is a gun and a girl. Whether or not he was being metaphorical is solely up to us but we can derive a certain popular lesson from that philosophy when it comes to the art of filmmaking ; sometimes less is more.

The oppositional philosophy that negates the “less is more” rhetoric is ; sometimes less is extremely difficult to attain. Especially when you are making cinema in a developing nation lodged in a perpetual state of socioeconomic crisis — you need more than a girl and a gun, you occasionally need a fist. Two filmmakers, Bayo Oduwole and Ife Olutayo understand this laborious dynamic more than anyone and in this piece we get to have a panoramic insight into the inner dealings of true indie filmmaking.

Every industry, regardless of size and profitability, inevitably creates its grassroots and miniature industry of youngsters. The byproduct of that is innumerable challenges that become increasingly prevalent and almost impossible to surmount. In current-day Nigeria and its ever-changing economic tide, there is no promise of permanence regarding the state of things but people push on despite and people have the urge the immutable urge to create in spite — “The hunger drives me and the access to control,” Ife Olutayo says when asked what moves him to make films given the austere system he creates within.

As tumultuous as it is to spearhead a production on his own, he enjoys the autonomy. To him, the net positive of creating within this system is intangible and tethered to posterity. When asked how he funds his film he says he is partly funded by an uncle in the United States who moonlights as an angel investor. He also writes screenplays as a way to for other directors and small film companies in Lagos that require his services as a way to consolidate any capital accrued for a film.

According to him, he shot his very film THE CANVAS using a minimalistic approach using a singular location and a DSLR Camera (which he said was cost effective) partly due to the inability to secure multiple locations for a grander narrative.

The challenges faced by Ife Olutayo were not dissimilar to Bayo Oduwole’s challenges. “I often joke with my collaborators that we make money to make films. That’s it. It’s the sink for our income, and we don’t mind, but that being said, while we’re still early in our careers, there’s only so much we can afford to do budget wise. We could attempt an indie feature but what money would be left for marketing this one, or filming the next? “Bayo states.

The commonality Bayo and Ife share is a drive against the reality of truly executing an envisioned cinematic idea, although there’s a certain disparity between them. Bayo Oduwole is a recent graduate of Ebonylife Creative Academy where he won best screenplay in his class, and Ife learned all he knows through watching and studying the revered and the greats. The essence of pointing out this disparity is to further enunciate how the challenges are a precedent and inescapable as a young filmmaker with no institutional structure or admiral’s fund.

When asked how he approaches filmmaking with a melange of hindrances before him, Bayo talks about planning, collaboration, contingencies and the ability to know when an instinctual approach is best suited for a vision.

”Without community, it wouldn’t exist. Without community, too many projects would probably never happen. Community keeps a lot of us sane and pushing.” Bayo says about what keeps them afloat and enthusiastic about the arduous process of creating a film. A common denominator here is resource or the lack thereof. This isn’t a denominator germane only to filmmaking in Nigeria, this country systemically hoards resources for its local artistes and talents but according to them there’s a certain amount allocated to those who make tent poles and blockbuster streamers.

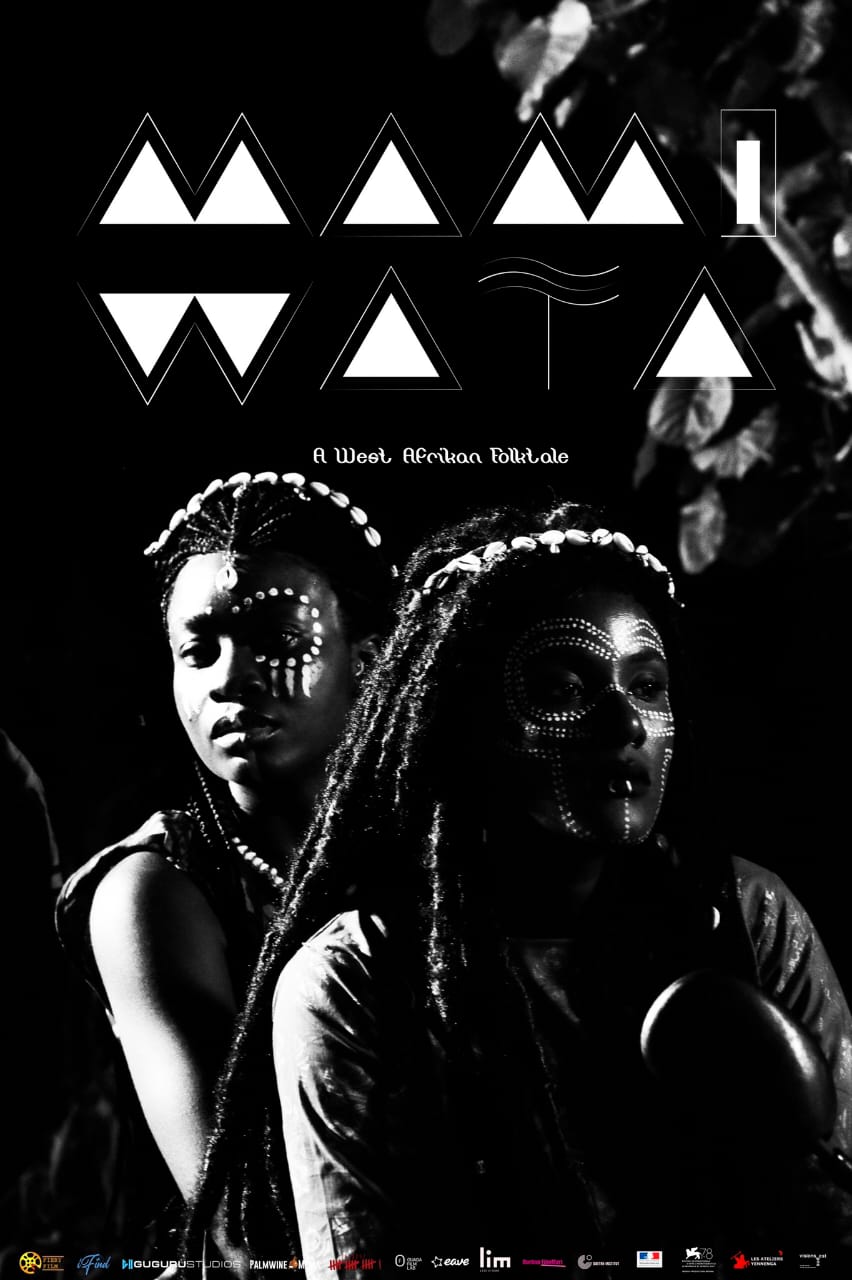

Some of the de facto leaders like Abba T. Makama(Juju stories) , C.J Obasi(Mami wata) etc who have gained considerable notoriety and international recognition still face hindrances and logistical impedance in their respective approach to the craft. The Nigerian screenings of Obasi’s Mami wata is an exemplary situation when we talk about the issues facing our independent filmmakers — the local theatres stifled his screening by slotting it in obscure viewing time frames or not showing it all in lieu of blockbusters.

This shows that even an established and critically – acclaimed Nigerian director will and can face a medley of problems post production. No one is truly exempt when you are dislodged or untethered to the norm or the product that sells and that is the grim reality one must for a while acquiesce with if you want to make films in Nigeria — unlike Godard, there’s no literal privilege of needing just a gun and a girl.

The austere inhibitions grow exponentially but it hasn’t trumped the will of Bayo Oduwole who was able to produce his prize-winning screenplay The last sane man in lagos and the grits of Ife Olutayo who is rapidly becoming an indie festival darling locally and in diaspora ; Liftoff First-time Filmmaker Sessions (virtual festival in London. Winner), Ibadan Film Festival (IFA), nominated for best experimental short in 2022, African film Society’s Classics in the Park in Ghana in 2023.

There are innumerable filmmakers out in streets of Lagos and past it, in obscure states and nameless towns, with sui generis visions, lacking the wherewithal and structure to bring them to concrete fruition. Each of them unfortunately beholden to the systemic incompetence of our nation and a lack of commensurate attention to the arts beyond what is palatable. If Nigerian cinema is to progress beyond its current status quo — if there’s to be a paradigm shift, those with the excess resources in film are morally obligated to help the next generation of filmmakers and their nascent visions and maybe making films won’t be, all pun intended, a long shot.