By Ifeoluwa Olutayo.

Some signs follow those who believe. Signs are all there, parallels along coastal cities, ruminations on ecological disaster, reimaginations of futures outside of capitalist expansion, and a critically assembled exhibit.

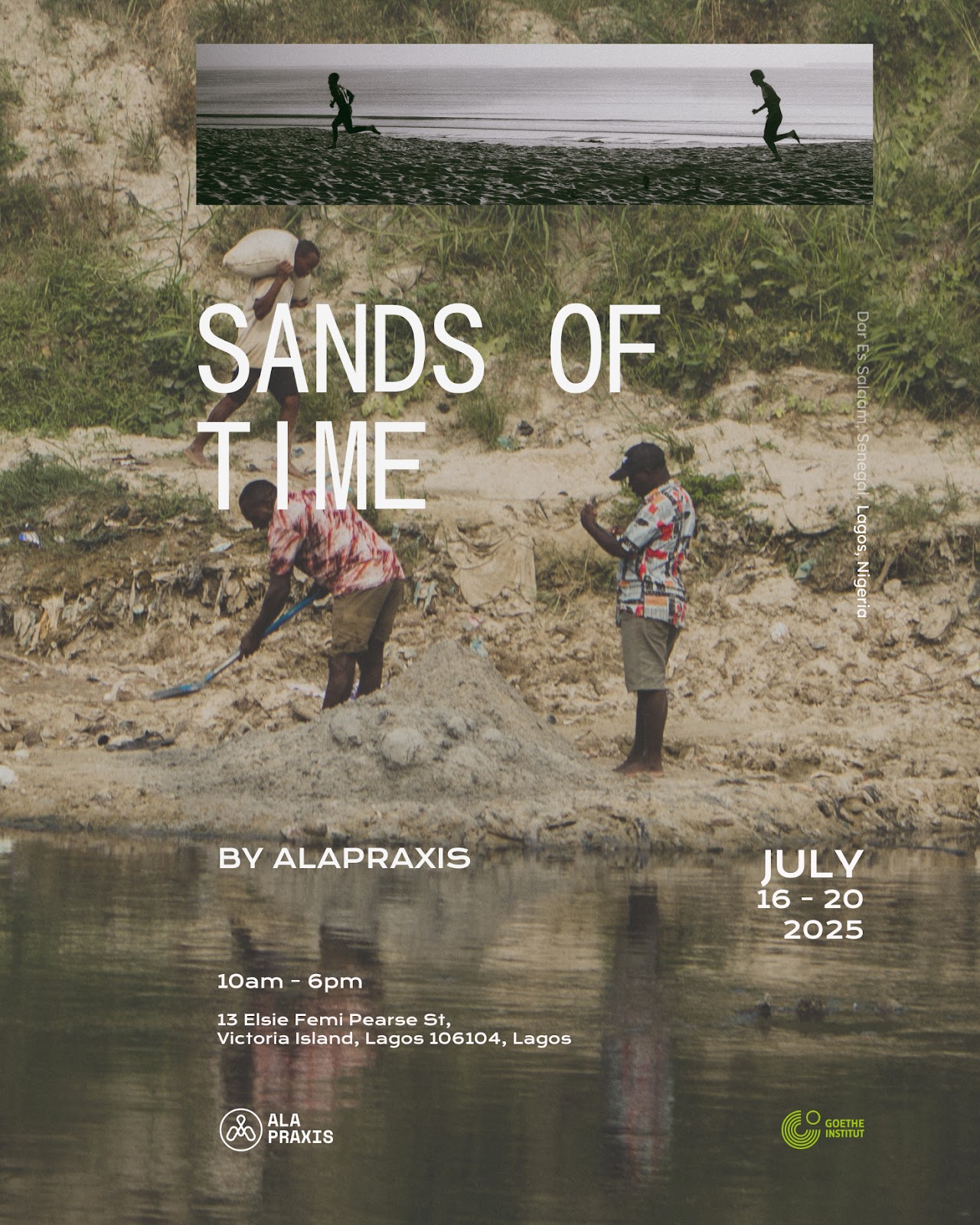

In the week that passed, Ala Praxis, a collective of artists and thinkers, brought their exhibition home to Lagos, titled Sands of Time. The Ala Praxis collective is made up of Jadesola Olaniyan, Josh Ike Egesi, Noah Misan Okwudini, Timilehin Osanyintolu, Peace Toba Olatunji, and Philip Fagbeyiro.

This body of work had been developed throughout a six-month residency courtesy of S+T+ARTS4AFRICA in Dar Es-Salaam, Tanzania, engaging the ecological impacts of the expanding construction industry in the coastal city. It had also travelled to Dakar, and it was finally brought home to Lagos, curated by Chinyere Obieze as part of the Dreaming New Worlds programme, of which Kedu Lagos was a stop of mine last November.

This iteration of the exhibition brings us into a consideration of the construction industry growing at an exponential rate across these two coastal cities, with the ecological consequences of the expansion of both cities.

Sand, despite presentation and popular notions, is a finite resource, but it is one that these expansion projects all around the world depend on. It’s in our buildings, our devices, our roads; silicon dioxide [silica] used in glass (which has so many uses) is found in sand.

Lines could be drawn from the flooding disasters in Lagos over the last couple of years to this growth, with expansionist projects like the Lakowe Lakes and Resort, and Eko Atlantic needing tonnes of sand for this project, dislodging communities and leaving destroyed aquatic ecosystems in their wake.

This constant exploitation in the name of growth is critiqued through their multi-media exhibit, along with questions about reevaluating whether cosmopolitan growth metrics like new skylines are more important than a sustainable relationship with nature and our environment. Parallels can be seen across the entirety of the exhibition, happenings all too familiar in Lagos, just as they occur in Dar Es Salaam.

Two films are on show at the exhibition: Sands of Time, produced by the collective and directed by one of them, Peace “Dopay” Olatunji & The Weight of Small Things by Noah Misan Okwudini and Prince Uhunoma Charles.

The former is an animated film, where we are thrust into a ruin of a world, explored by an astronaut, who walks this lonely path, rediscovering structures and spaces lost to disaster. A meditation on the consequences of our exploitation is voiced in Swahili, personalising the subject exploited, and expanding to the ruin we bring closer and closer. The latter explores these concepts and more, structured around exchange, a player in capitalism. It ruminates on the paltriness of our currency’s exchange for the lifeblood of the earth, and how what is taken in return is our safety, spaces, and world, a forceful possession in response to our lack of consideration.

Images travel from Dar Es Salaam to drive home the point. Our lack of consideration is now creating ruins in the present, as described by the collective.

In the images, we are guided through Dar Es Salaam’s relationship with nature. Striking images of ruins built alongside rivers, which have now suffered aquatic-ecosystem death and drying up due to the sand mining on their shores, offer us a vivid look at the cost of our take-and-take relationship with the environment. The sand used to advance the city’s modernity results in an erosion of shorelines that also chokes sealife and affects the living situations along the banks of these rivers and the sea.

Growth in this sense accelerates the destruction of the landscape, displacing communities that have possibly been settled around these (previously touted) sources of life and work. Their memories and connections to the space become disconnected, half-forgotten within the decaying halls of these ruins.

There are also images of sediments – remnants of decaying aquatic ecosystems–superimposed (screenprinted) on kangas, fabric native to Tanzania and other parts of East Africa; kangas are known rather famously in those parts, as the cloth that speaks. With these images, mounted above in the exhibition space to look up at, we’re faced with the loss shown rather simply through this fabric of communication. The ruins also give us an opportunity to see the disasters wrought in the present, also to reevaluate the path we’re on and the systems that facilitate the creation of such ruins.

We are posed with questions as we look at the Ruins of The Present (the title of the first of three series on display): Is our short-term advancement worth the long-term detriment of our environment? Is our treatment of a finite resource as infinite truly the path to any future worth living in? Well, the ruins, present in this moment, answer the latter.

The lens turns to the second series, named Rituals of Digging. Images show the rhythm of the process of sand mining, with a rather striking image of note, one that frames the process ongoing with the background being the city, skylines standing ominously, as if in expectation of new jutting structures to join.

Sand mining comes with its risks and consequences: loss of arable land, collapse of structures in the immediate area, health risks, and exploitation outside of regulated mining systems. It is also in this image that I find class imbalances, as the decisions about this extraction are made in rooms far away from those who work hard to earn a living mining this sand for use in the cities.

It is also these people whose communities get displaced and bear all the consequences of this changing (for the worse) landscape as the environment is shaped into ruin. They work honestly into their displacement and loss, a chilling symptom of capitalism’s sick reshaping of our communities.

As Felix Guattari described in his work– quoted by Jean-Pierre Bekolo in his manifesto, Cinema As a Transformational Tool for the Therapeutic Intellectual– capitalism is an intrinsically violent and destructive system that reinforces inequality and exploitation, and we must think of alternative economic structures that prioritize collective wellbeing and ecological sustainability. This is ever more present as we consider our (coastal) cities and their tools of development.

The third series considers the Dance of the Shorelines. We see how many residents in Dar Es Salaam engage with the beaches of Dar Es Salaam, a key third space in some of their daily lives. We see joy, work, and routine all scattered in these images. Fishermen (Wavuvi) fish in the water, and as the collective describes, there are no lines between work and their ideas of community, with their catch shared equally at the end of the day.

It brings to mind many of the previous questions, one of which is what sort of communal spaces we stand to lose with this constant expansion, sand taken from beaches like these, to build a world increasingly tailored for individuality.

It reminds me of a similarly violent (very much so) situation in Lagos with the Landmark beaches, where entire beaches were destroyed last year to make way for a coastal road and not only were third spaces lost (increasingly privatized but still), but small communities displaced, some of them losing their source of livelihood to this destruction. We must reconsider our approach to progress.

At the centre of the exhibition is the hourglass, a technically fabulous contraption assembled using materials sourced within Dar Es Salaam, including plywood, pine, and medium-density fibreboard (MDF), with supporting rods made from aluminium, and central bulbs made of acrylic. Attendees interacted with this structure, heaping sand at the top, which flowed back down into the heap at the bottom, symbolising, as described by the collective, balance and reciprocity. It is, in a sense, a continuation of the advocacy of rethinking our relationship with the environment as one that needs balance.

Ambient sounds echoed in the exhibition space, bringing sounds from Dar Es Salaam. The sounds of waves, the beach and the birds; all of these plant the listener in the city, bringing the city to Lagos.

Sands of Time challenged us to look at the world we live in and reconsider short-term progress for long-term sustainability. We only have the one, after all.

Narratives abound, and signs were present.

What signs?

Technical dexterity, ecological consequences, fabric advocating balance, a world of joy and community, and the reconsideration of perceived gains in a world that is clearly losing.