By Akinwande Jordan

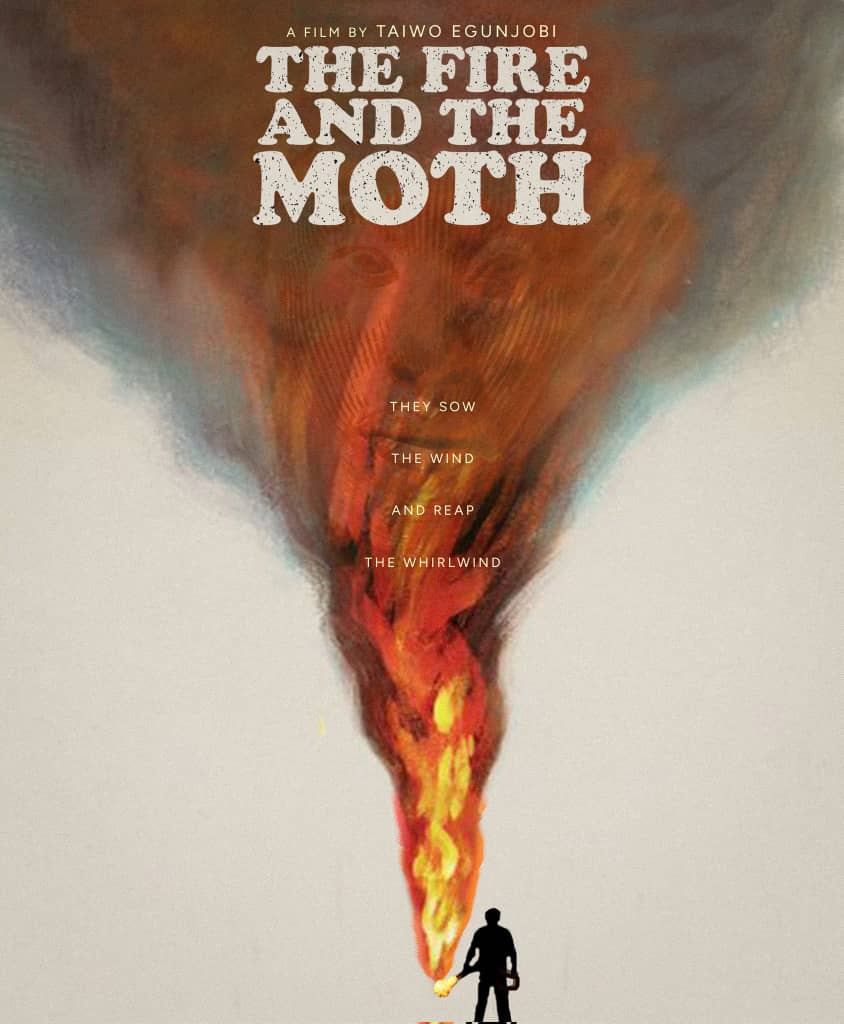

Poster for The Fire and The Moth by Taiwo Egunjobi

Afopiná tóní oun ó pa fitila, ara ẹ ni yóò pa – YORUBA ADAGE.

The man is waiting in his car. He is waiting in a coffin. He’s waiting in his solace of trade. He is waiting in this anarchic, godless world. He is waiting in an Edenic expanse of land, where nature reminds you of the possibility of a grand designer —a communion of spirit and necessity. He is waiting in the cauldron that holds the brutal evolution of things. He is waiting in a world devoid of comfort and eternal tenderness.

The man deals in the movement of artefacts; we say that for legal reasons. The man is into the fringe exports of a lost empire. The man is wounded. The man is in the cosmic dire straits of crime. Behind him, in the confines of the shadows, in the frame of the law, in the machinations of karmic enforcement is a bloodhound of a police man whose daemonic gaze darts past all creatures great and small, into the souls of deviants who believe the law is an ass. This is Taiwo Egunjobi and Isaac Ayodeji’s design. You should know this when you are settled —or better yet, unsettled, to see this film.

“If the rule you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?” – Anton Chigurh, No Country for Old Men

Off the unbroken momentum of A Green River (2023) — a visual masterclass in simmering thrills and psycho-political horror elements set in the cutthroat 1980s — this duo have once again stepped up to the plate for collaborative excellence, for a switchblade of a film, for a statement: we are the best in the business.

The film follows the savage adventures of Saba (Tayo Faniran), a smuggler with an ill father who is embroiled in the typical deal gone wrong with a rare Ife bronze head. Behind him is Opa (Olarotimi Fakunle), a venal demon of a policeman who seeks to covet the bronze head for profit. Ini Dima-Okojie plays the forlorn Abike, who regards the bronze head as a pathway to greener grass for her and her sister. Jimmy Jean Louis’s Jef Costello-esque presence as a mercenary with no name imbues the film with an impalpable tension.

Fadamana Okwong’s cinematography is an expressionist Pygmalion from the aliveness of the aerial still shots encasing the verdant terrain of our characters, to the serene suspense consecrating the landscape vista Saba trudges through, to the nigh corporeal embodiment of pure evil that is Opa, the frantic policeman from hell.

Egunjobi and Isaac Ayodeji construct a world within Okwong’s eyes, where the rules of natural law are futile and moribund upon use. Where the lands are chanting an unforgiving tune. Philosophically, a Hobbesian impulse drives every character despite themselves. Even the staunchest of saints are moths drawn to the fire of hubris and desperation, towards the leveraging of a debris of history and the indelible nature of greed. And this impulse is ouroboric, a serpent swallowing itself, knowing death is merely an occupational hazard.

The neo-western and noirish cinematic influences are apparent if you are familiar with the lay of the land; No Country for Old Men (2007) by the Coen Brothers (and Edward Zwick’s Blood Diamond) is especially conspicuous in the visual grammar and the godlessness that is evoked in film. No performance is wasted on the usual suspects of excess and filler scenes.

Tayo Faniran’s Saba keeps his head on a swivel, like an Arthurian knight, a criminal Sir Gawain if you will, on a quest for glory. Ini Dima-Okojie brings sufficient sport to counterbalance Tayo Faniran’s demonstrably stoic approach to his character. Olarotimi’s Opa Stephens stands out in the cast of characters — you almost commit the blasphemy of comparing to Anton Chigurh.

Still, he’s significantly more strident and motivated by a set of ends justified by nefarious means; there’s no pessimism to him. Yes, he’s a bloodhound, a demon wolf, a rotten stooge of a rotten system armed to the teeth, bespectacled like Agent Smith in The Matrix, but he’s searching for El Dorado, too. All the characters are. You can hear it in the silence of God as the plot creeps towards that which signifies nothing.

The distinction between The Fire and The Moth and the other Taiwo Egunjobi and Isaac Ayodeji collaboration, aside from the Faulknerian title, is the coming-of-age in style and substance. You can perfectly track the metamorphosis of vision and the fear of under-exploration through the avant-garde and the conventional. There’s no overt aversion to interrogating what appeals to them visually and philosophically. One may correctly assume that they know a film can be entertaining, yet a thesis on the human condition and its numerous vagaries. This film, in particular, answers the question posed by its neo-western influence; there are no rules.

There’s always a man in a car. There’s always a plot. There’s always a piece of history that will bring about our deaths.