by Akinwande Jordan

Robbers and cops, banks and supposedly impenetrable vaults, the adrenaline rush of being an outlaw as the plans go awry, the hero, the impactful crew, the treachery, the descent from controlled chaos to abject confusion — Hostage films are a cornerstone in the action and thriller genres across the major film industries. We love Pacino’s love-induced one-man showdown in Sidney Lumet’s Dog day afternoon. We adore Clive Owen’s poetic cunning in dismantling a bank’s security system in Spike Lee’s Inside Man or Bruce Willis as John Mclane in Die hard shooting his way through German terrorists on an ever-wintering yuletide.

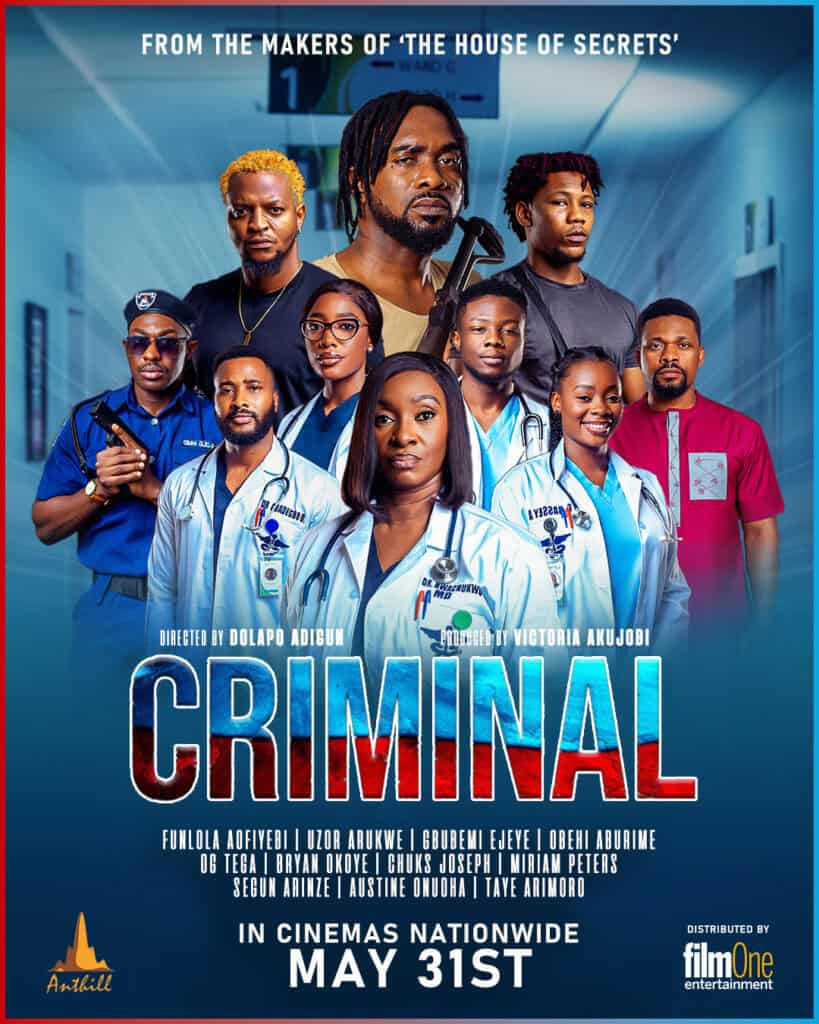

With the hostage film, you have the vicious forward flow towards escape or the Jaws of the law. You investigate the crime as you enjoy the plot; you root for the law and outlaw simultaneously because, well, you contain multitudes. Under Anthill Studios, the Niki Akinmolayan-penned and Dolapo Adigun-directed Criminal attempts to recreate that jolting experience but it does not understand the poetry of the formula, only the generic application.

At the prestigious Greenleaf Hospital, Dr Amara Nwachukwu (Funlola Aiyebi) faces an emergency situation that ensues when an influx of victims of a grisly road accident in varying critical conditions arrives. Some arrive at the doors of death. Included in the victim pool is a pregnant woman in need of fetal intervention and despite the valiant effort of Dr. Nwachukwu, they are plunged into a crisis situation.

The crisis situation was worsened by the arrival of Uzo (Uzor Arukwe) and his gang of robbers walk into the eye of the current situation with his bullet-wounded brother (Austin Onuoha) forcefully demanding prompt medical attention. They proceed to take the medical staff and victims hostage to expedite the outcome of their demands.

The premise is presented as simple and executable. All the elements are intimate and should by all narrative logic create a nail-biting and skin-crawling sensation of anxiety as you watch the showdown at the hospital unfold. Yet, CRIMINAL feels like the cinematic equivalent of an over-dramatised impromptu play conjured up by hyper-imaginative school kids obsessed with playing cops and robbers with wooden guns and paper handcuffs. It brazenly falters in delivering any iota of high-stakes or psychological turmoil pertinent to the subgenre. This, however, is no fault of tyro director Dolapo Adigun who can be pardoned by virtue of inexperience —much of the disaster is embedded in the script itself as one can almost envision it as written for the sole purpose of dazzling or being the “first of its kind” in the Nollywood ecosystem. The ambiguity of the plot blights the watching experience.

As readers and possibly cinephiles of varying tastes, remember that a film should primarily have aesthetic value regardless of cinema philosophy and plotless unfolding has no actual bearing on cinematic quality. Conversely, a plot-oriented film with glaring gaping holes in the plot is a cardinal sin even the pope cannot vanquish with the holiest of litanies.

Uzo’s bullet-wounded brother could have been treated by any of the medical staff and yet there was a demand for the good doctor Amara Nwachukwu as if the god of medicine had blessed her to treat flesh wounds; this specific demand by name also establishes a sense of familiarity between Uzo and Amara, this familiarity or its origin was never hinted or even subtextually addressed in the unfolding of events. Loose ends and question marks floating around the plot like cancer cells in blood. Hostage films that end in a police standoff have to earn the battle of guns; even the old Nollywood films about gangsters and law enforcement in a fiery stalemate understood that it had to be earned — that the scenario, though with a predictable outcome, had to emerge from the demands and the counter-demands, the mutable nature of power dynamics, the psychological brawl between the hostage-takers and law enforcement and the possibility of the doublecross. All these elements do not exist here in CRIMINAL or maybe they exist in small incoherent doses improperly mixed.

Be that as it may about the narrative blunder, Funlola Aiyebi and Uzor Arukwe deliver quality performances despite being armed with blunt daggers. A testament to their professionalism because it is a true miracle that they uttered some lines that did not cause them to chuckle. Criminal is a pretty film. That is said without contempt.

Entertaining enough to keep the average audience sat and attentive. The shots evoke novelty or a thirst for it at the very least. Beneath the daze of the artificial chaos, you can see how it truly wants to be good and profitable. The quintessential blockbuster. But at the end, as the credits roll after the high of the entertainment, you feel as though you’ve witnessed the poor treatment of a bullet wound.