by Akinwande Jordan

In the regressive ecosystem of Nigerian romance, women are often represented by antiquated tropes and moralising archetypes. With a directorial/writing ensemble of Dika Ofoma, Uzoamaka Power, Victor Daniel, and Olamide Adio, the collaborative efforts of Zikoko and Bluhouse studios have made the valiant attempt at deconstructing and depicting the complexity of cultural expectations, autonomously, and the interior lives of women.

Adapted from first-hand accounts by real people who have featured in the famous Zikoko Life section —these are their stories… sort of:

The first Zikoko Life short, What’s Left of Us, written by Victor Daniel and co-directed with Olamide Adio, is an unflinching look at a marriage in slow decline. Aliyu (Caleb Richards) and Mariam (Tolu Asanu) reach a deadlock when Mariam decides she does not want any more children.

The striking opening scene, in which Mariam slips into the bathroom to take a contraceptive pill, sets the contentious tone for what we are to expect in this marriage. Asanu plays the character with a blank stare and a sigh that suggests exhaustion more than secrecy. It is a routine born from necessity, the quiet calculation that silence is safer than confrontation.

Aliyu, already involved with Fatima (Joy Sunday), reacts to the discovery of the pills with anger and expels Mariam from the house. The film resists moral neatness, but it is clear about the cost of asserting bodily autonomy. Too many men, like Aliyu, reduce women to bi-functional tools: sexual partners and child-bearers. Mariam’s refusal to be absorbed into those roles is met not with dialogue, but with emotional exile. Zikoko lays out the power imbalance without hesitation or sentimentality.

Something Sweet, written and directed by Dika Ofoma (A Quiet Monday), shifts to a gentler but equally fraught dynamic. Leke (Ogranya) is captivated by Ziora (Michelle Dede) from the moment they meet. His affection is direct and unwavering, but Ziora greets it with skepticism.

The idea of a man in his twenties loving a divorcee with a teenage son seems implausible to her, despite the reciprocity. The obstacle is not love itself, but the shape it is expected to take. Ziora hesitates, measuring her desires against the pressures of propriety, while her son and Leke’s mother voice their disapproval. Ofoma draws out these tensions patiently, showing how love can be possible yet still stall under the weight of social scripts and inherited rules.

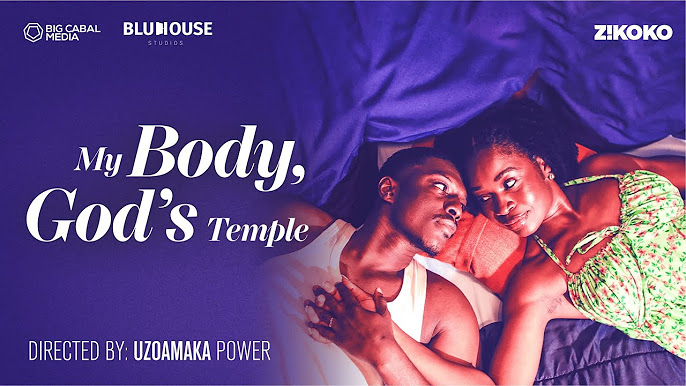

Zikoko Life’s third entry, My Body, God’s Temple, Uzoamaka Power assumes the rare triple role of writer, director, and lead actor, crafting a film that unfolds with the intimacy of confession and the the surgical precision of a character study.

At its centre is Omasilu, a devout Christian woman who keeps her vow of chastity until marriage, believing this act of restraint to be both holy and protective. Yet when the moment arrives, what should be a consummation becomes a source of unease. Years of being told that her body is God’s temple have etched a deep and immovable association between sex and defilement, leaving her unable to approach intimacy without shame.

Power doesn’t sensationalise this struggle. Instead, she allows it to emerge gradually, showing how Omasilu’s faith and upbringing, while central to her identity, have also created an internal barrier she must learn to navigate if she is to fully inhabit her marriage.

The connective tissue that coheres this Zikoko anthology is the simultaneous loss and gaining of identity. Identity serves as a salient focal point as each character spends the better part of every film resisting and/or conforming to cultural structures they have hastily categorised as preordained.

The Zikoko Life films aren’t preoccupied with sermonizing, and each director presents a variance in visual grammar. Everything is an installation of the personal within the expansive context of the externalized. Ofoma is concerned with the identity of aging in the false age of overpriced youth. Daniel and Adio are interested in the identity of a woman defying the so-called biological imperative.

Uzoamaka Power takes arms against the gendered precepts of faith and the poisonous church within the body. You might probably leave as a logical misogamist upon watching the films or an empathetic hopeless romantic skeptical of tradition as we know it. Either way, it gives you pause.