by Emmanuel Olutimileyin Odebunmi

Growing up in Nigeria in the early 2000s, I witnessed movie culture back when it was still in its Nolly-classic era. This was the age of DVDs and film clubs, cultists and OG ritualists. It was the age of veterans like Rhamsey Nouah, Kanayo O Kanayo, Stephanie Okereke, Nadia Buhari, Jim Iyke, Van Vicker, Pete Edochie… the list goes on. The early 2000s are for Nollywood what the 90s are for Hollywood – the time everyone wants to go back to.

As technology and film culture globally evolved, so did the film industry in Nigeria. The CDs and film clubs were the first to go. The loyal customers who reliably visited the movie rental clubs every Friday right after picking up the kids from school started to dwindle. Families still bonded over movies every weekend and during holidays, but they began to do so with DSTV and its counterparts. There used to be equal spacing for urban plots and traditional stories in the industry, but at this stage, traditional stories started to be relegated. More and more urban-centred movies were filmed and marketed. The audience started to want something different. Something newer. And the industry raced to give it to them.

With communication technology bridging gaps between the Nigerian entertainment industry and the rest of the world, Nigerian entertainment had to compete with Western industries for the attention of the people. For a time, Nollywood seemed to lose some of its former novelty. It began to be a phenomenon for older demographics, with the younger viewers hopping on Western crazes and trends. This nudged the Nigerian film industry into its next era, which was that of numerous comedy series and superstar soap operas like Tinsel.

Tinsel ran between 2008 to 2013 and passed the baton to its successors in the years proceeding. By this time, Nollywood had settled into the prime time of sitcoms like Jenifa’s Diary, The Johnson’s, and attractive drama titles like The Husbands of Lagos, The Mens Club, and the popularly beloved Skinny Girl in Transit. These productions caught and held the attention of Nigerians and, at the same time, gave Nollywood a place even as the world continued to spin faster and faster.

The way I see it, the industry had three eras. Its OG classic era, its in-between era, and finally, the industry of today. Today’s Nollywood is the most exciting it has ever been. The industry has its hands in the genesis of various new undertakings that it is hard to keep track of. Regardless, one thing is sure – Nollywood is well on its way to becoming a global phenomenon that might even be able to give Hollywood a serious run for its money in a matter of years.

While it is obviously such a time for the industry, one can pick out a recurring theme in the movies being released today – the Lagos Noir. We have previously had movies of similar genres and themes populate the market at different time periods. This happened with romcoms like Isoken, The Phone Swap, The Royal Hibiscus Hotel, When Love happens… I could go on and on.

With Lagos Noir, however, one could say that we haven’t seen anything like this since the OG times of the early 2000s. Lagos’ crime streak and underground stories are of the inherent peculiarity that they cannot possibly be told by anyone who isn’t authentically one of us – a native Nigerian who has actually lived here. A remarkable number of the most influential movies of recent times either have a hint of this theme or the plots are completely based on it. What’s more, it seems to be a honey pot that Nollywood’s filmmakers are collectively digging into, and it is giving back satisfactorily.

The industry is enjoying a fast metamorphosis. For that, however, Caesar has to be given his due. This new age of Nigerian movies was progressively motivated by the effort of different factors and personalities. Filmmakers like Kemi Adetiba, Rhamsey Nouah, Kunle Afolayan, Niyi Akonmolayan, Jade Osiberu, Kayode Kasum, Tunde Kelani, and so many others securely held down the fort and were able to not only tell stories that sparked the fire of the industry but to also make movies that seemed to bring everyone together again to collectively appreciate Nigerian stories.

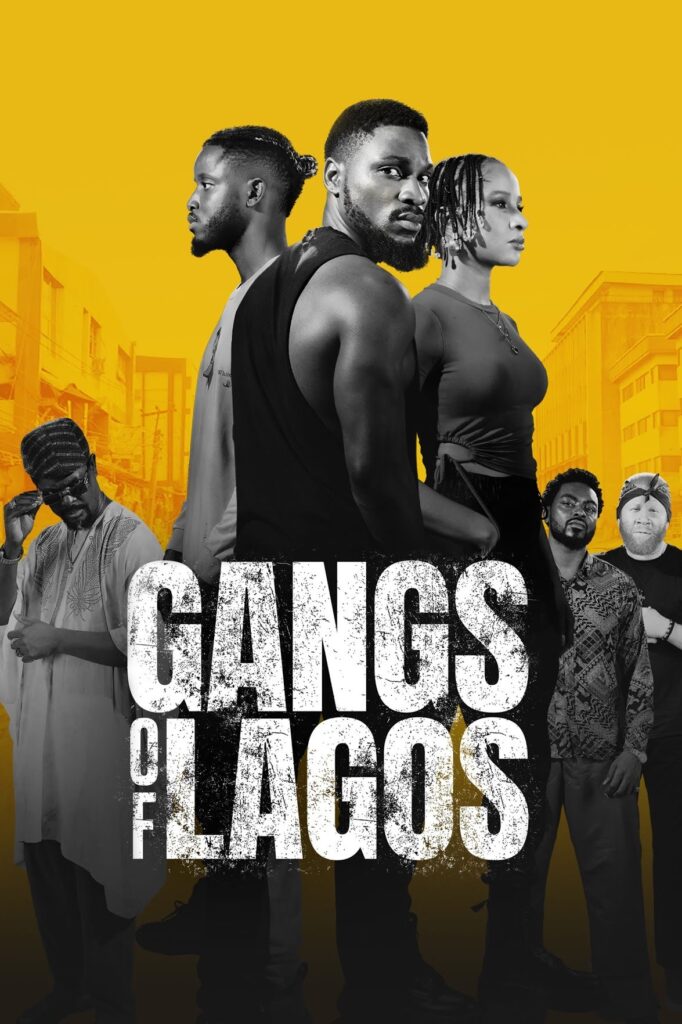

Wedding Party caused a frenzy. Citation inspired a feeling of belonging because of its setting. King of Boys was a phenomenon. Living in Bondage marinated nostalgia and served it as the most tasteful cocktail of cinematic goodness. Sugar Rush left a trail of excitement and fun. Ayinla was a masterful work of art, and have you seen the charts? Movies like Brotherhood and Gangs of Lagos are blazing new fires worldwide. So unprecedented was the fact that Gangs of Lagos was number 2 on the South Korean charts earlier in the month of April.

Another usher into the new age is the rise of a new crop of young GenZ filmmakers like The Critics, Ikorodu Boys, and so many other unnamed artists who are out there telling their own stories and doing their own authentic thing.

These factors are combined with the last but certainly not the least – the advent of streaming services and the recent injection of African stories into film festival culture. The industry has been given an unprecedented boost, the effects of which we are yet to fully see. One of the most recent that I was particular about was the premiere of Elesin Oba, a native language film, at the Toronto International Film Festival. The premiere inspired a moment of pride in me, and it begged the question: why would anyone not take this chance to invest in the industry like it is the new Bitcoin?

For the average audience member, the truth about an industry isn’t found in the statistics or even in the numbers. No. The truth lies in the perceptions and conversations. Before the average man or woman or millennial or genZer buys into anything, they listen to the chatter – which nowadays is usually the newest thing being said on Twitter or in their various niche circles. From where I am standing as a GenZ filmmaker with dreams of having my own stories being told on the big screen, Nollywood has evolved into a nesting place for the collective hope and intention of generations of filmmakers, and it is determined to raise itself unto a new pedestal that would rival its past heights and demand reverence from film lovers worldwide while still telling its unique and authentic stories, and I am here for it.